Health Lessons From the World’s Blue Zones

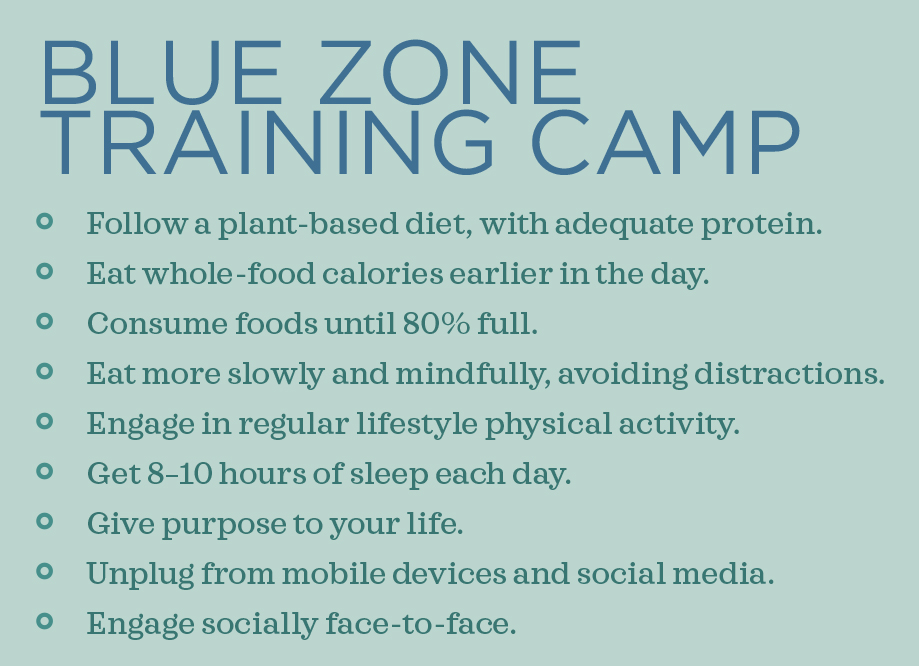

Reinforced by research, nine lessons from the Blue Zones can lead to longer, healthier, more fulfilling lives.

| Earn 1 CEC - Take Quiz

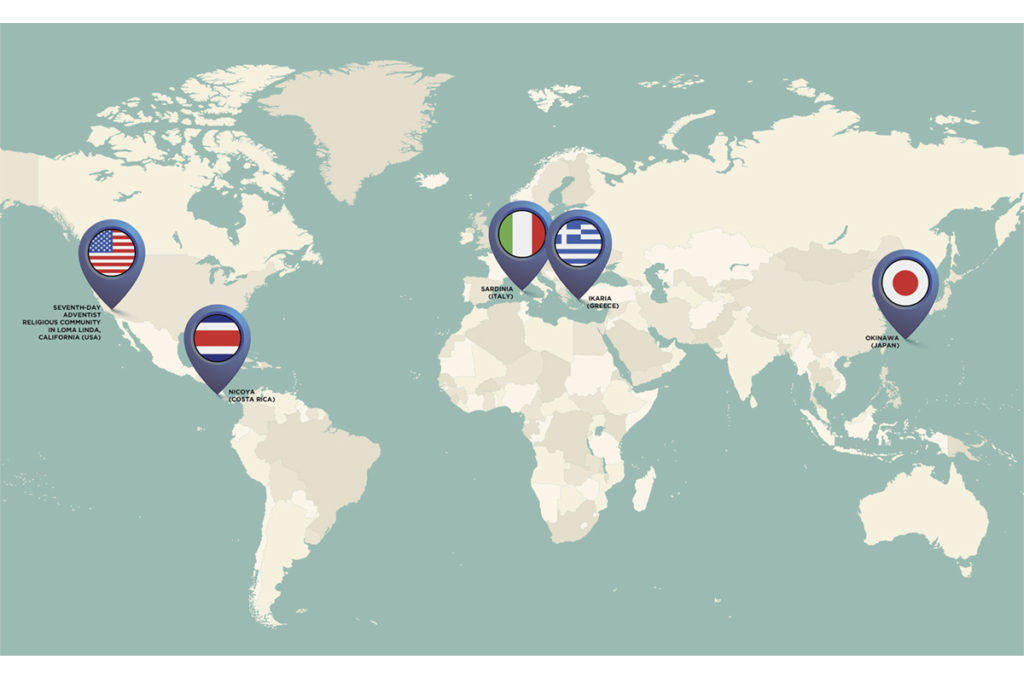

There are regions around the globe where pockets of people appear to enjoy a longer, healthier life expectancy. In these so-called Blue Zones, residents statistically live the longest and produce nonagenarians (ages 90–99) and centenarians (100 years old and above) at seemingly extraordinary rates. The specific areas are Okinawa (Japan), Sardinia (Italy), Nicoya (Costa Rica), Ikaria (Greece) and the Seventh-day Adventist religious community in Loma Linda, California (USA) (Willcox et al. 2006; Poulain et al. 2004; Buettner 2008).

The patterns of behavior that suggest there are practices we can adopt to live well, for longer, were chronicled by explorer Dan Buettner and a team of anthropologists, demographers and epidemiologists. Buettner originally presented his findings in a 2005 National Geographic article, then described them in greater detail in a book, The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who’ve Lived the Longest (National Geographic 2008). Buettner has since published a handful of other books devoted to the eating and lifestyle habits that characterize people noted for longevity and happiness in Blue Zones pockets around the globe.

What is especially interesting is that Buettner and other longevity researchers continue to identify a number of common threads that bolster health and happiness and help secure an above-average life expectancy. These threads show that it’s about more than winning the genetic lottery.

“Our genes don’t ultimately determine our fate; instead, it’s the behaviors we engage in daily and the environment we live in that play a bigger role in life span,” says Keith Diaz, PhD, assistant professor of behavior medicine at Columbia University Medical Center.

What can the latest research teach us that supports lessons gleaned from people who consistently live longer than average? Quite a lot, as it turns out, especially in comparison with a typical U.S. lifestyle.

1. Plant-Based Diets Predominate in Blue Zones

Diets in the Blue Zones are predominantly plant-based.

When discussing longevity, diet is a good place to start, since it’s an entrance ramp to better health. The average tofu-laced menu in Okinawa may differ from what’s on offer in a Costa Rican village, where beans and rice dominate, but Suzanne Dixon, MPH, MS, RDN, a senior medical writer and epidemiologist with Cambia Health Solutions in Portland, Oregon, says a parallel among Blue Zones is that diets are predominantly plant-based.

“Eating a diet based on minimally processed plant foods is associated with both the longest life spans and the longest health spans,” Dixon explains. She stresses that, apart from a large number of Seventh-day Adventists in the Loma Linda zone, most Blue Zone residents aren’t strict vegetarians; they just eat meat less often and in smaller portions (Pes et al. 2015). Legumes, whole grains, and local garden vegetables and herbs are the cornerstones of all these eating styles, including the Mediterranean-diet variant preferred by elders in Ikaria, Greece. A constant flow of modern-diet research supports this eating approach (Smith 2017), as opposed to the standard American diet, which is inundated with greasy fast food and sugar.

A 2019 study determined that adults who adhered to a healthy plant-based diet (more whole grains and fewer processed carbohydrates) benefited from a lower risk of early death from ailments like heart disease (Baden et al. 2019). Similarly, an investigation in JAMA Internal Medicine that followed almost 71,000 middle-aged Japanese adults for an average of nearly 20 years found those who ate the most plant protein were 13% less likely to die prematurely than those who ate the least (Budhathoki et al. 2019). Other studies involving Seventh-day Adventists have linked a vegetarian lifestyle (without red meat) with a lower chance of early mortality (Orlich et al. 2013; Alshahrani et al. 2019).

“There are many reasons why a plant-based diet is good for your health, but the presence of hundreds to thousands of disease-risk-reducing phytonutrients is a big one,” says Dixon. “A lower calorie density that contributes to the maintenance of lower body weight through the life cycle also helps, as does the presence of a healthier balance of fatty acids and multiple types of fiber, which seems to support a healthy microbiome for improved immunity.”

Action points: Look for ways to add more plants, and slice out some of the meat. Wedge in a few meatless meals each week and serve smaller portions—3–4 ounces—of meat rather than the large portions typical in the American diet.

Dixon says the key to achieving the effects of a Blue Zone–type diet lies in the proportions of food types consumed. “About two-thirds to three-quarters of the plate’s surface should be covered by plant foods,” urges Dixon. “Instead of what comes in a package, focus on minimally processed plants, including vegetables, fruit, legumes and whole grains.” She also advises being adventurous: Try plant foods from around the world to make this way of eating more exciting.

See also: 5 Big Benefits of Plant-Based Diets

2. In the Blue Zones, Most Calories Are Eaten Early in the Day

Blue Zone residents tend to eat their largest meals earlier in the day and their smallest meal at night.

The long-living people of Nicoya and Loma Linda tend to eat their largest meals early in the day and end with smaller dinners (Buettner 2008). Compare that pattern to the results of a study using data from 872 middle- to older-age people. Consuming a higher percentage of daily calories within 2 hours of waking in the morning was associated with a lower risk of being overweight or obese compared with consuming a bigger chunk of daily calories within 2 hours of going to bed (Xiao, Garaulet & Scheer 2019).

This is an important finding, considering that a 2019 report from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development revealed that rising rates of obesity will, by 2050, shorten life expectancy by almost 3 years in all the countries analyzed, and by nearly 4 years in the United States (OECD 2019).

“Not going right to bed soon after your biggest meal of the day may provide some metabolic advantages,” says Dixon. For instance, many of us will burn more calories earlier in the day, when our metabolism is higher, whereas calories we consume at night may go to fat stores.

Action points: Try eating more of your calories earlier in the day. It may be a good idea to “eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince and dinner like a pauper.” That means making the daybreak meal higher in whole-food calories, then scaling down from there—and skipping late-night snacking.

See also: Skipping Breakfast Creates Nutrition Gaps

3. Mindful, Slower Eating Defines Meals

People in the Blue Zones integrate eating into socializing in a more leisurely way than we tend to do here in the U.S.

It’s not just what we eat that matters, but also how we eat. Great-great-grandmothers in the Japanese archipelago of Okinawa aren’t wolfing down lunch while scrolling through their social media feeds. They tend to practice the undistracted mindful approach called hara hachi bu, which is eating until you are 80% full.

“People in the Blue Zones integrate eating into socializing in a more leisurely way than we tend to do here in the U.S., and this may have the same effect [as] intentional mindfulness, in that it slows people down so they eat less overall,” notes Dixon. “One key benefit of eating mindfully is being more aware of fullness cues so you are less prone to overeating,” says Dixon.

This point is supported by an investigation that found people working toward mindful eating (fully tuning into their thoughts, emotions and physical sensations) were able to practice better portion control of energy-dense foods (Beshara, Hutchinson & Wilson 2013). Mindful eating also allows Blue Zones denizens to experience more joy from the food on their plates.

Action points: Find ways to heighten awareness during mealtimes. Unplug from the TV and smartphones while eating; consume meals in calm, quite places; and chew food more slowly (giving the body a better chance to recognize satiety signals). “Setting your utensil down [after] every single bite will increase awareness and enjoyment of the meal,” advises Dixon.

See also: Helping Clients Enjoy the Taste and Culture of Food

4. Physical Activity Fills the Day in Blue Zones

It can be said that people in the Blue Zones live rewardingly inconvenient lives.

Physical activity in all Blue Zone areas involves a consistent flow of natural movements, including those involved in gardening, pounding corn by hand to make tortillas, practicing tai chi daily and shepherding livestock in the hills. (Men in Sardinia tend to outlive women, and that could be thanks to the herding work most males do.) It can be said that people in the Blue Zones live rewardingly inconvenient lives.

Diaz is adamant that this type of low-grade “survival” exercise is more crucial than a couple of planned exercise sessions during the week. “Our physiology was not designed to be idle for long periods of time, which happens when we sit for most of the day,” he notes.

Researchers reported in the British Journal of Sports Medicine that, for each additional 30 minutes of sedentary time on a typical day, men were 17% more likely to die during a 5-year study period. However, each extra half-hour of light activity, such as walking, was associated with 17% lower odds of death (Jefferis et al. 2019). These statistics suggest that doing even light physical activity is worthwhile for extending life span.

Further, 75-year-old lifelong exercisers (those who have exercised regularly year after year) have similar cardiovascular health to people three decades younger (Gries et al. 2018). And an investigation from the American Cancer Society reported that older adults who walked 2.5–5 hours per week had a lower risk of dying from cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and cancer than those who were not active. Walking as little as 2 hours per week also reduced the risk of suffering a life-shortening disease (Simon 2017).

“Frequent exercise and less sedentary behavior are critical for controlling body weight, regulating blood sugar and improving blood circulation, all key factors in disease prevention,” explains Diaz. Not to be overlooked is how a stroll in a local park can do wonders in bringing down stress levels.

Participating in higher-intensity activities may also pay off. Tour de France bicycle riders, accustomed to taking part in vigorous activity, lived an average of 17% longer (81.5 years versus 73.5) than the general population (Sanchis-Gomar et al. 2011). “The best exercise profile may involve a combination of frequent movement and some higher-intensity sessions,” says Diaz.

Action points: Get up and move, often. Beyond going hard at the gym for an hour a day, engineer more movement in daily life—and encourage clients to do the same. Take stairs instead of the elevator, go for a stroll while talking on the phone, embrace an active hobby (like gardening or bird-watching) and set a timer to signal movement breaks after sitting for more than an hour. Cycling or walking to work or the gym is also a smart move.

See also: Light Activity for Older Women’s Mobility

5. Sleep Nourishes Lifestyles

People in Blue Zones generally get a good night’s sleep and take naps.

Sleep is much more than a luxury. “It has emerged as a key health behavior we should be paying more attention to,” says Diaz. People in Blue Zones regions typically obtain the recommended 8–10 hours of sleep each night, and long-living Ikarians are known for cherishing their afternoon naps. In contrast, more than a third of American adults are getting less than 7 hours of sleep each night, according to the CDC (2016).

Poor sleep habits don’t just affect mental functioning; they can also chip away at life span. A large research review found that people who typically sleep less than 7–8 hours a night are at higher risk for cardiovascular disease and early mortality (Kwok et al. 2018). A separate study found that adults with hypertension or type 2 diabetes—which describes many millions of Americans—had twice the likelihood of dying from heart disease or stroke if they got fewer than 6 hours of sleep per night (Fernandez-Mendoza et al. 2019).

“Sleep is critical to the body’s rejuvenation process and also other health aspects we still don’t understand,” Diaz says.

What’s more, there’s a reason donuts seem especially enticing if you’re sleep-deprived: Even one night of lost slumber affects how the brain processes food rewards, leading people to view junk food more favorably when they’re tired (Rihm et al. 2019). Over time, poor food choices triggered by lack of sleep increase obesity risk and associated health woes.

Action points: Practice good sleep hygiene. The key is establishing a bedtime routine that is conducive to sleep: Refrain from digital devices at least 1 hour before bedtime, remove light pollution from the bedroom and designate an earlier sleep time.

Fitting in an afternoon nap habit can also be good. Swiss researchers found that people who napped once to twice weekly for 5–60 minutes had only about half the risk for cardiovascular disease compared with those who didn’t nap at all (Häusler et al. 2019). It may be that napping lowers stress hormone levels.

See also: You Are How You Sleep: The Cost of Sleep Deprivation

6. Purpose Defines a Long Life

Benefits that accompany purposeful living can drive health and longevity.

Nicoyans call it plan de vida, and Okinawnas refer to it as ikigai, both of which essentially translate to “a reason to live.” Elders who begin each day with a sense of purpose and fulfillment, while recognizing how they contribute to their communities, seem to live long lives, or at the very least feel positive, upbeat and happy. Turns out, lessons from the Blue Zones may be as much about the quality of years as the quantity.

“We all need a good reason to get out of bed in the morning,” says Jack Guralnik, MD, PhD, MPH, professor of epidemiology and public health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. He adds that many of the things that accompany purposeful living, such as reductions in stress and depression and an increase in social activity, can drive health and longevity. “This Blue Zone concept goes hand-in-hand with improving your psychological health.”

While Guralnik admits it’s challenging to prove a direct link between finding one’s purpose and aging well, there is some research to show it helps. For example, after evaluating strength of purpose in about 7,000 adults over age 50, researchers assigned life-purpose scores to the participants. Five years later, those with the lowest scores were about twice as likely to have died as those with the highest scores. A low score for purpose was also associated with greater mortality from heart disease (Alimujiang et al. 2019).

Action points: Find and cling to your purpose. When providing clients with health history forms, add a question dealing with their life purpose. A sense of usefulness can come from something as simple as designing and implementing new programs at your gym, immersing yourself in a hobby, or actively volunteering time to worthy causes. Crafting a personal mission statement can guide the way.

See also: Life Purpose is Linked with Longevity

7. Nature Nurtures Active Lifestyles

Being outside in green space can lessen the risk for a number of ailments.

Whether they’re gardening, herding sheep or taking a stroll in the mountains, Blue Zone people typically spend ample time outdoors. Although they live in climates conducive to being outside, most desk-bound Americans could do better by embracing Mother Nature, regardless of where they live. Americans, on average, report that they spend 87% of their time indoors and an additional 6% enclosed in their vehicles (Klepeis et al. 2001).

British researchers found there is enough evidence to suggest that frequently being outside in green space—defined as undeveloped land with natural vegetation and urban green areas like city parks—can lessen the risk for a number of ailments, including type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease (Twohig-Bennett & Jones 2018). And according to a study published in Scientific Reports, spending at least 2 hours a week in a natural environment can greatly enhance a person’s overall sense of well-being (White et al. 2019).

“Going outside frequently can work indirectly to increase our health by acting as a buffer against stress and promoting increased rates of physical activity,” says Guralnik. It also can help people soak up more vitamin D. While the jury is still out with respect to the sunshine vitamin’s role in fending off disease, there is research hinting that adequate vitamin D levels may play a role in increasing life span (Pilz et al. 2016; Chowdhury et al. 2014; Schöttker et al. 2013).

Action points: Get outside, and encourage others to enjoy the great outdoors. Move some client training sessions to a nearby park, join a community garden, take up a sport like mountain biking or hiking, walk in an urban green space during lunch breaks, and embrace active commuting (cycling or walking to work).

See also: 6 Reasons Why Nature Might be the Best Gym

8. People Connect in Person in the Blue Zones

People in the Blue Zones depend less on their electronics and more on face-to-face social interactions.

The only Blue Zone in the U.S. is the home of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, a denomination that observes Sabbath, a day devoted to fellowship with God, family, community and nature. It’s no secret that most Americans are seemingly always connected; the average person spends nearly 4 hours a day staring down at a mobile device (He 2019).

The potential stress, distraction and negative mental health effects of being tethered to our devices and the constant fast-paced shifts in focus it encourages should not be taken lightly. “People need to ask themselves what they are doing while always on their devices, namely being sedentary, isolated and not eating mindfully,” cautions Diaz. “It’s easy to see how, over time, this behavior is potentially detrimental to health.”

For an investigation carried out at the University of Pennsylvania, 140 people continued their regular use of social media platforms or were limited to 10 minutes a day (per platform) on Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat (30 minutes total). The people who trimmed their social media use (which, in turn, should have reduced screen time) reported feeling less lonely, anxious and depressed, as well as experiencing less “fear of missing out,” or FOMO (Hunt et al. 2018). A separate study found that the link between social media and depression was largely mediated by a “social comparison” factor (Steers, Wickham & Acitelli 2014).

Action points: Look for ways to curtail use of digital devices and social media. For example, implement a daylong break from digital devices 1 day per week, use monitoring apps such as RescueTime to cut down on smartphone time, turn off most push notifications, and never bring the phone into the bedroom. Use your newfound time to go for a walk, cook more meals and engage in face-to-face time.

See also: Smartphones and Poor Eating Habits

9. Social Circles Reinforce Health

Create an environment that encourages daily socializing with family and friends.

Buettner and other researchers have identified social interactions as a major player in Blue Zone longevity (Buettner 2005; 2008). The Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda live in tightknit communities, while Okinawans have their moai, a social circle meant to provide support during life stressors and reinforce shared healthy behaviors. These communities focus on face-to-face time and not Facebook likes.

An investigation in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found a dose–response association between having more social relationships and being at lower risk of testing poorly on physical health measures—including blood pressure, waist circumference and inflammation—both early and later in life. Conversely, subjects with fewer social connections and more social isolation were at increased risk for health-hampering inflammation and hypertension (Yang et al. 2016).

“Loneliness really gets under your skin, and the depression it encourages can accelerate aging to the same degree as health conditions like high blood pressure or high blood sugar,” Guralnik explains, “and people with fewer social connections are also typically less physically active.”

Humans are social creatures hardwired to thrive on social interaction. When we don’t get it, the stress can eat away at our mental and physical health. With that said, it should be noted that the number of daily social interactions most Americans are having has steadily declined in recent decades. From the rise of social media to longer work commutes, the reasons for family discord and receding friendships are many.

Action points: Create an environment that encourages daily socializing with family and friends. Schedule weekly get-togethers with friends, nudge clients who appear lonely to join a group exercise class, volunteer for a cause that forces interaction with others or join a sports league that involves group play. And find ways to enjoy more of your meals in good company.

“In the Blue Zones, each eating opportunity is a time for connection with others, being with family and friends, and a time for gratitude for all of the good things in their lives,” Dixon says. The key is for people to surround themselves with a like-minded tribe that practices the right behaviors, since healthy lifestyle habits are contagious.

See also: Training Happy for Positive Behavioral Change

Blue Zone America

“We aim to engage policymakers in both small and large communities to implement the evidence-based, necessary changes in the local environment that make healthier lifestyle choices easier for people,” says Nick Buettner, director of the Blue Zones Project. To date, 50 communities in North America are actively involved, “but there are about 1,000 more who are eager to work with us,” he notes. Buettner says the multiyear “big-picture” ventures can include everything from designing local roads that foster active transportation to overhauling restaurant menus to offer more nutritious meal options.

Examples of measurable outcomes have included a 40% drop in healthcare claims by city workers in Albert Lea, Minnesota; a 13.5% reduction in smoking rates in Fort Worth, Texas; and a 64% lower rate of childhood obesity in Beaches Cities, a coastal area of Los Angeles. As Buettner is quick to point out, these changes can translate into huge healthcare savings down the road. The Well-Being Index data shows Iowa’s Blue Zone communities are outpacing the nation in overall well-being.

“To work, communities need to have the right leadership, be willing to invest in the necessary resources and have accountability as a way to measure progress,” Buettner says. Learn more about this longevity project at bluezonesproject.com.

Promote Blue Zone Values

Increasingly, scientific research supports the anecdotal evidence emerging from the Blue Zone longevity pockets. Many of the lifestyle habits that have historically kept Ikarians and Nicoyans healthy into old age also have practical application in our fast-paced modern world.

When applying the Blue Zone tenets to your life or to the daily routines of your fitness clients, keep in mind that each category is part of an integrated whole, a way of living. We need to help others maintain positive patterns of various behaviors over time. As Diaz is quick to point out, “No workout at the gym will make up for endless hours of sitting, eating poorly and living life in isolation.”

We can’t all live in the Sardinian countryside herding goats, but it’s possible to build Blue Zone values into your own life and the lives of your fitness clients as simple approaches to promoting the longest, healthiest, most fulfilling life possible.

References

Alimujiang, A., et al. 2019. Association between life purpose and mortality among US adults older than 50 years. JAMA Network Open, 2 (5), e194270.

Alshahrani, S.M., et al. 2019. Red and processed meat and mortality in a low meat intake population. Nutrients, 11 (3), pii: E622.

Baden, M.Y., et al. 2019. Changes in plant-based diet quality and total and cause-specific mortality. Circulation, 140 (12), 979–91.

Beshara, M., Hutchinson, A.D., & Wilson, C. 2013. Does mindfulness matter? Everyday mindfulness, mindful eating and self-reported serving size of energy dense foods among a sample of South Australian adults. Appetite, 67, 25–29.

Budhathoki, S., et al. 2019. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a Japanese cohort. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179 (11), 1509–18.

Buettner, D. 2005. The secrets of long life. National Geographic. Accessed Sep. 26, 2019: bluezones.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Nat_Geo_LongevityF.pdf.

Buettner, D. 2008. The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who’ve Lived the Longest. Des Moines, IA: National Geographic.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2016. 1 in 3 adults don’t get enough sleep. Accessed Oct. 2, 2019: cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0215-enough-sleep.html.

Chowdhury, R., et al. 2014. Vitamin D and risk of cause specific death: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort and randomised intervention studies. BMJ, 348, g1903.

Fernandez-Mendoza, J., et al. 2019. Interplay of objective sleep duration and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases on cause-specific mortality. Journal of the American Heart Association, 8 (20).

Gries, K.J., et al. 2018. Cardiovascular and skeletal muscle health with lifelong exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 125 (5), 1636–45.

Häusler, N., et al. 2019. Association of napping with incident cardiovascular events in a prospective cohort study. Heart, 150, 1793–98.

He, A. 2019. Average US time spent with mobile in 2019 has increased. eMarketer. Accessed Oct. 2, 2019: emarketer.com/content/average-us-time-spent-with-mobile-in-2019-has-increased.

Hunt, M.G., et al. 2018. No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37 (10), 751–68.

Jefferis, B., et al. 2019. Objectively measured physical activity, sedentary behaviour and all-cause mortality in older men: Does volume of activity matter more than pattern of accumulation? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53 (16), 1013–20.

Klepeis, N.E., et al. 2001. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): A resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology, 11 (3), 231–52.

Kwok, C.S., et al. 2018. Self-reported sleep duration and quality and cardiovascular disease and mortality: A dose-response meta-analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association, 7 (15).

Murphy, S.L., et al. 2018. Mortality in the United States, 2017. NCHS Data Brief, 328 (Nov.). Accessed Sep. 26, 2019: cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db328-h.pdf.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2019. The heavy burden of obesity. Accessed Oct. 15, 2019: oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/the-heavy-burden-of-obesity_67450d67-en.

Orlich, M.J., et al. 2013. Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173 (13), 1230–38.

Pes, G.M., et al. 2015. Male longevity in Sardinia, a review of historical sources supporting a causal link with dietary factors. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69 (4), 411–18.

Pilz, S., et al. 2016. Vitamin D and mortality. Anticancer Research, 36 (3), 1379–87.

Poulain, M., et al. 2004. Identification of a geographic area characterized by extreme longevity in the Sardinia island: The AKEA study. Experimental Gerontology, 39 (9), 1423–29.

Rihm, J.S., et al. 2019. Sleep deprivation selectively upregulates an amygdala–hypothalamic circuit involved in food reward. Journal of Neuroscience, 39 (5), 888–99.

Sanchis-Gomar, F., et al. 2011. Increased average longevity among the “Tour de France” cyclists. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 32 (8), 644–47.

Schöttker, B., et al. 2013. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and overall mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Ageing Research Reviews, 12 (2), 708–18.

Simon, S. 2017. Study: Even a little walking may help you live longer. American Cancer Society. Accessed Sep. 30, 2019: cancer.org/latest-news/study-even-a-little-walking-may-help-you-live-longer.html.

Smith, S.D. 2017. Recommending plant-based diets. Canadian Family Physician, 63 (12), 916.

Steers, M-L.N., Wickham, R.E., & Acitelli, L.K. 2014. Seeing everyone else’s highlight reels: How Facebook usage is linked to depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33 (8), 701–31.

Twohig-Bennett, C., & Jones, A. 2018. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environmental Research, 166, 628–37.

White, M.P., et al. 2019. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Scientific Reports, 9 (1), 7730.

Willcox, B.J., et al. 2006. Siblings of Okinawan centenarians share lifelong mortality advantages. Journals of Gerontology A: Biological and Medical Sciences, 61 (4), 345–54.

Xiao, Q., Garaulet, M., & Scheer, F.A.J.L. 2019. Meal timing and obesity: Interactions with macronutrient intake and chronotype. International Journal of Obesity, 43 (9), 1701–11.

Yang Y.C., et al. 2016. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 113 (3), 578–83.

Matthew Kadey, MS, RD

Matthew Kadey, MS, RD, is a James Beard Award–winning food journalist, dietitian and author of the cookbook Rocket Fuel: Power-Packed Food for Sport + Adventure (VeloPress 2016). He has written for dozens of magazines, including Runner’s World, Men’s Health, Shape, Men’s Fitness and Muscle and Fitness.