The Body-Mind Cube

Runners and swimmers, dancers and gymnasts, bodybuilders and bowlers. None of them are likely to be described as body-mind fitness types. In books on the topic (Iknoian 2001; Seabourne 2001), membership in the “body-mind fitness club” is largely reserved for those who practice yoga, tai chi, Pilates, qigong or some martial art.

To borrow Susan Powter’s (1995) phrase, we simply have to “stop the insanity.” By locating the essence of body-mind in particular exercise forms, such as yoga, rather than seeking this essence in all forms of exercise, we perpetuate a divisive mythology. More poignantly, by labeling exercise forms either body-mind or not, we create a prejudicial hierarchy (“These are better for you because they are body-mind!”) that blinds us to the extraordinary potential for any type of physical movement to be conscious and mindful. Doesn’t it make sense for us to teach exercisers how to be mindful in whatever they do, rather than trying to shepherd them all into yoga or Pilates classes?

Body-Mind Exercise: Activity or State of Mind?

I have a friend who bowls every week. He averages over 220. I didn’t know this when he invited me for an evening of fun. That night he had a “bad back,” so we bowled only three games. His scores: 245, 267, 258. I don’t want to tell you mine. We didn’t have beer, and I can honestly say he was more mindful than a number of scantily clad classmates I’ve had in Bikram yoga. Along these same lines, tennis rarely makes the cut for inclusion in body-mind exercise. Yet, in 1974, Tim Gallwey wrote a classic book called The Inner Game of Tennis, representing many of the qualities we currently attach to “body-mind” exercise forms to justify their classification.

In my lifetime, I have practiced tai chi, aikido, meditation and yoga, along with running, biking, swimming, aerobic dance, modern dance, volleyball, softball and bowling. I have found mindfulness in them all at different points and been personally enriched by each of them. When I combine my own experiences with research (Gavin & Mcbrearty 2006) and the commentaries of thousands of exercisers and sports participants whom I have interviewed as a researcher, some core themes emerge that guide me toward an understanding of body-mind exercise.

What Makes Movement Mindful?

Body-mind exercise is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon. Just as one may daydream, fall asleep or worry about problems when sitting in meditation, so too in any physical activity one’s mental processes may range widely. Mindfulness may be influenced as much by an exerciser’s preoccupations or intentions as by the nature of the activity itself. Two implications flow from this: First, mindfulness is best understood as a “more or less” quality represented as a percentage of the time mindfulness is experienced during training. Second, identifying the qualities that make an exercise experience mindful may be more useful than trying to catalogue activities.

Now to a more practical question: How do we characterize mindfulness? I want to propose three dimensions that seem particularly relevant to whether a participant is having a mindful physical experience while exercising:

- Focus. Is the mind internally or externally focused? Put another way, is the participant paying attention to what’s going on inside or outside herself? Ten years ago, in a serious discussion on the nature of body-mind fitness, a group of industry colleagues concluded that it required “an internally directed mindset.” As a member of that group, I have had second thoughts about this position and hope to show you why.

- Judgment. Is the participant judging or evaluating what he is experiencing, or is he in a nonevaluative, nonjudgmental state of mind? Judgment takes many forms. One can be assessing the competition in a game, comparing oneself with others or evaluating oneself against performance benchmarks. In these cases, the mind is somewhat outside the experience and positioned as a critic or a judge.

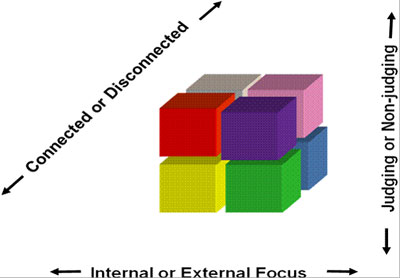

- Connection. Are the participant’s mental activities related to what she is doing with her body—or are the two disconnected? Picture someone reading a magazine while pedaling a stationary bicycle; now think about a gymnast performing on a balance beam. In the first case, the mind is quite disconnected from the body’s experience, while in the second, body and mind are likely to have merged. If we consider each dimension from an either-or perspective, there are two representations of each: internally focused or externally focused, judging or nonjudging, connected or disconnected. Put these together and we have a Body-Mind Cube (below) made up of eight minicubes or categories. Using this cube, we can ask how much of a participant’s mental time is spent in each category while engaged in a fitness activity or sport.

Let’s see how it works by considering individuals doing hatha yoga. Even though yoga is typically considered a body-mind exercise, the participants’ mental activities will ultimately determine whether in fact it will be.

The Body-Mind Cube

Since an internal focus is often attributed to body-mind exercise, let’s first consider the four varieties of internally focused experience.

Category 1: Internally Focused, Nonjudging, Connected. This combination of mental activity might be found when a participant focuses inward on thoughts or bodily sensations that are connected to a posture, and when they maintain an accepting, nonjudgmental attitude. Most body-mind practitioners would probably characterize this as a mindful experience.

Category 2: Internally Focused, Nonjudging, Disconnected. Even though the participant may have an internal and nonevaluative focus, the conditions needed for a body-mind experience are unlikely to be met when thoughts are disconnected from bodily actions.

Category 3: Internally Focused, Judging, Connected. Imagine the participant focusing on a yoga posture, but with thoughts full of evaluation or even self-criticism. Even though two of the three conditions for a body-mind experience are evident, the presence of judgment or evaluation (in almost any form) moves us away from what would commonly be regarded as pure body-mind exercise.

Category 4: Internally Focused, Judging, Disconnected. In this instance, the person may be critically reviewing the day’s events or experiencing judgment about something unrelated to the posture. In essence, the mind is disconnected from immediate experience and the participant is in a state of judgment. Doesn’t sound very body-mind, does it?

While body-mind exercise is often thought to have an internal focus, we know that in practices like meditation, participants may be asked to focus externally on a sound or a visual image. It’s also true that many martial arts are considered body-mind exercise—and these definitely require practitioners to pay attention to what’s happening outside of themselves.

Let’s see how the four representations of externally focused experience show up in our analysis.

Category 5: Externally Focused, Nonjudging, Connected. Imagine a participant looking at a point in space as an aid to holding a balancing posture, without judgment if he falls and with his mind totally connected to his yoga practice. This qualifies fully as a body-mind experience.

Category 6: Externally Focused, Nonjudging, Disconnected. This may look like someone gazing without judgment at a classmate. The participant’s body may be moving appropriately, but her thoughts are disconnected from her actions. This experience is not body-mind and has similarities to the body-mind split evident in a person reading a magazine while pedaling a stationary bike.

Category 7: Externally Focused, Judging, Connected. As in category 3, the thoughts the participants have may be related to what they are doing, but their thoughts are evaluative, comparative or judgmental. In this regard, the experience lacks an important ingredient for body-mind activity.

Category 8: Externally Focused, Judging, Disconnected. In this final category, participants have not only separated mind from body but are also in a state of judgment or evaluation. I think you can call this one pretty easily.

Multiple Options for Mindfulness

The Body-Mind Cube clarifies some important issues. For a start, it isn’t necessary that participants have an internal, almost meditative focus to achieve mindfulness. That’s simply one type of body-mind experience. Another occurs when participants are focusing on something outside themselves that informs their physical actions, so their outward mental attention is intimately linked to what their bodies are doing. This is perhaps clearest in examples from the martial arts. In fact, body-mind focus is likely to occur as a kind of oscillating inner-outer awareness. For instance, the martial artist or yogi may focus externally for cues to action and internally on body dynamics almost simultaneously.

Another key dimension of the Body-Mind Cube is the absence of evaluation, judgment, comparison or investment in the outcome. So, on second thoughts, maybe my bowler friend wasn’t so body-mind. He got pretty upset when some of the pins stubbornly refused to fall. In my personal experience with aikido training, I have come to realize that the times when I am strongly invested in throwing my partner to the mat are the times I feel least body-mind. Ultimately, the mind can be focused externally or internally, but it needs to be free of attachment to judgments, attitudes or results. In other words, one is in that wonderful paradoxical state of being a participant-observer.

A final feature of the cube relates to the body-mind connection itself. Sports psychologists identify this as associative vs. dissociative thinking (Weinberg & Gould 2003). Doing a body scan while running is referred to as associative thinking, while looking at the scenery to distract oneself is known as dissociative thinking. True body-mind exercise exemplifies associative thinking, yet doing exercise that is generally presumed to be body-mind doesn’t guarantee mindfulness.

As you work with clients, know that mindfulness occurs naturally and often in most physical activities—if only for moments at a time. With your professional guidance (see the sidebar “Globalizing Body-Mind” below), clients can increase the percentage of time they are training mindfully—that is, able to release attachments and judgments and be fully present—no matter what exercise or sport they are engaged in. And by adding just seconds of mindful training each day, your clients will receive a great gift.

Body-mind exercise can be realized in virtually all physical activities, not just those with centuries-old traditions, such as yoga and qigong. While it is true that many Western exercise forms were originally developed with a lopsided emphasis on biomechanical science, it is actually not that difficult to engage the mind in rote, repetitive exercises such as stair climbing or stationary cycling. As fitness professionals, you can facilitate mindfulness in clients through the prompts you offer in classes and the guidance you give during one-on-one instruction. Here are some simple ideas:

- Encourage clients to focus on their breathing while exercising.

- Teach clients how to conduct body scans while training. For instance, “Focus your awareness on the muscles in your face—ask them to relax. Now, focus on your neck and shoulders—and ask them to relax.” From there, continue through the rest of the body.

- If clients habitually listen to music while exercising, suggest they try meditational soundtracks that will center them rather than distract them.

- Help class participants live the experience by cuing them to focus their attention on bodily sensations and in-the-moment awareness.

- Support participants in creating rituals that will allow them to leave their preoccupations in the locker room. Guide them toward making their exercise time an experience in meditation.

- Encourage clients to count repetitions or repeat phrases such as “in, out” or “up, down” while weight training.

- Teach clients who participate in competitive sports how to play their games in the moment, detaching themselves from the outcome and maintaining an acute awareness of sensory cues and experiences.

Jim Gavin, PhD, IDEA contributing editor, is a health counseling psychologist and professor of applied human sciences at Concordia University in Montreal. He directs the Personal and Professional Coach Certification program offered through Concordia.

References

Gallwey, W.T. 1974. The Inner Game of Tennis. New York: Random House.

Gavin, J., & Mcbrearty, M. 2006. Exploring mind-body modalities. IDEA Fitness Journal, 3 (6), 58–65.

Iknoian, T. 2001. Mind-Body Fitness for Dummies. Foster City, CA: IDG Books Worldwide.

Powter, S. 1995. Stop the Insanity. New York: Pocket Books.

Seabourne, T. 2001. Mind/Body Fitness: Focus, Preparation, Performance. YMAA Publication Center.

Weinberg, R.S., & Gould, D. 2003. Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.