Break Up a Sedentary Day With Active Standing

Research shows that standing is not enough; movement is the key to client gains.

It is an inspiring time to be a fitness professional. Now, more than at any other time, we have scientific evidence that physical activity and exercise are tremendously beneficial for managing and reducing chronic diseases, improving brain health, lowering blood pressure, reducing depression and anxiety, controlling obesity, and more. How do we help people gain these benefits? Three scientific reports begin to define a road map of where we are headed to effectively combat sedentary lifestyles.

Sedentary Behavior Terms Clarified

As the young science of studying sedentary behavior evolved, researchers realized that there was a need for consistency in terminology and standardization of techniques. Enter the Sedentary Behaviour Research Network, an organization connecting researchers and health professionals from around the world who share an interest in sedentary behavior research (SBRN 2017). At press time, the SBRN had 1,748 members (sedentarybehaviour.org).

The following are three key terminology definitions related to sedentary behavior research (Tremblay et al. 2017).

- Sedentary behavior is any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure of 1.5 METs (metabolic equivalents) while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture (see “Energy Expenditure Continuum,” below). A MET (expressed as 3.5 milliliters of oxygen consumed per kilogram of body weight per minute, or mL/kg/min) is a method of describing the energy expenditure of activities performed by people of different weights in a way that makes the measurements comparable regardless of weight variations.

- Physical inactivity is an activity level insufficient to meet present physical activity recommendations. For adults, this means not achieving 150 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity per week or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week (or an equivalent combination of vigorous- and moderate-intensity activity).

- Standing is a position in which one is maintaining an upright position while supported by one’s feet. Passive standing refers to any waking activity in a standing posture that expends 2.0 METs, such as standing in a conversation, standing in a line or standing at a religious service. By contrast, active standing refers to a standing posture with an energy expenditure 2.0 METs, such as standing while lifting weights, standing on a ladder and/or standing while performing tasks at a workstation (e.g., on an assembly line).

How Much Energy Is Required to Go From Sitting to Standing (and Back)?

As fitness pros, we regularly encourage clients to sit less, stand more and move a lot during their waking days. A unique area of research seeks to quantify the metabolic benefits of interrupting sitting time with frequent bouts of standing.

METHOD

In an original investigation, Júdice et al. (2016) recruited 50 men and women volunteers, ages 20–64, with no known diseases, to fulfill three randomized 10-minute conditions (in one session). Participants were instructed not to engage in any exercise, ingest any caffeine or take any type of stimulant for 48 hours prior to the study and not to consume any calorie-containing beverages or food for 8 hours before the session.

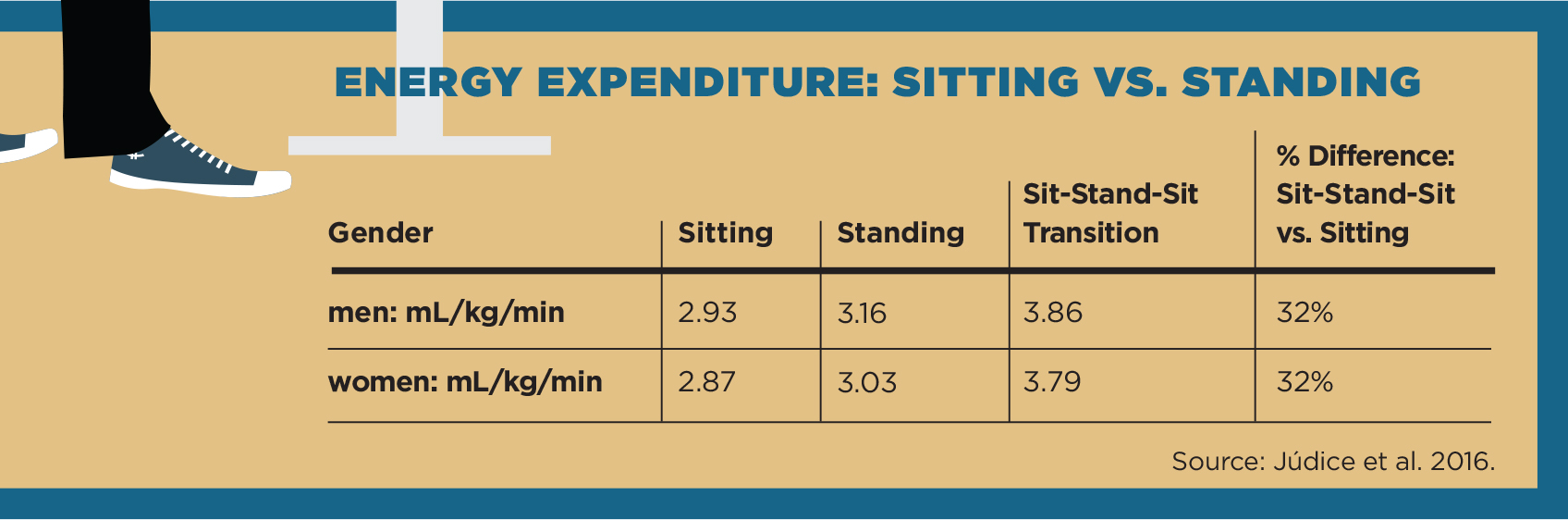

The three conditions were (1) spending 10 continuous minutes standing motionless with arms resting along the sides of the body; (2) spending 10 continuous minutes seated in a chair, motionless, with hands on thighs; and (3) performing 10 sit-stand-sit transitions during 10 continuous minutes by standing up from a seated position and returning to the seated position in one single-action movement at the 30-second mark of each minute. The data on oxygen consumption (mL/kg/min), grouped by sex, is depicted in “Energy Expenditure: Sitting vs. Standing,” below.

FINDINGS

Perhaps the most noteworthy finding from this study is that completing 10 sit-stand-sit transitions (during a 10-minute period) expends 32% more energy than just sitting for 10 minutes—for both men and women. Júdice et al. extrapolate that the additional energy expenditure (during the 10 minutes) is about 3.2 kilocalories. The study authors also recap previous research showing that, on average, a typical office worker transitions from sitting to standing (and then returns to sitting) 52 times a day, using about 16.6 kcal in energy expenditure. These data confirm that, over the long run, increasing the number of these transitions daily will contribute positively to caloric output. Interestingly, continuous standing yields only slightly higher energy expenditure values than continuous sitting for both men (8% higher) and women (6% higher).

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Although standing workstations are gaining wonderful popularity, their benefits appear to be better realized in body posture, alignment and work productivity than in caloric output. For enhancing energy expenditure, the public health message should be to interrupt sustained periods of sitting with sit-to-stand transitions and, of course, to progressively add more movement once standing.

See also: Startling Data on Sedentary Behavior

Does Reducing Sitting Time Help Thwart Type 2 Diabetes in Older Populations?

Type 2 diabetes management involves concentrated lifestyle modifications, which include weight loss, moderate-intensity cardiovascular exercise and resistance training. Currently, very little is known about type 2 diabetes prevention in adults over the age of 75, and moderate levels of physical activity may be too challenging for them to achieve. A recently published investigation by Bellettier et al. (2019) provides some thought-provoking findings.

METHOD

In this study, researchers tracked 6,116 ethnically diverse, community-dwelling women ages 63–99 using accelerometers (devices designed to objectively quantify physical activity) over 24 hours a day for up to 7 days.

FINDINGS

A major finding was that the women who were most sedentary on a daily basis had two times higher odds of having diabetes than the women who were least sedentary. Additionally, those who were sedentary for the longest sustained blocks of time had the highest odds of having type 2 diabetes.

INTERPRETATION

When a person sits for long periods without getting up, the major weight-bearing muscles of the legs are not contracting. With no muscle contractions, these muscles cannot efficiently utilize the sugars and fats circulating in the blood. Sustained over time, this leads to overweight/obesity and type 2 diabetes. Reduced blood flow from inactivity eventually creates an unhealthy environment for the body’s blood vessels, increasing the risk of peripheral artery disease and blood clots.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Clearly, the findings by Bellettier et al. show that interventions targeting sedentary behavior are essential for quality of life as people age.

Fitness pros should encourage older clients to break up long sitting bouts with light-to-moderate activity because this appears to be highly associated with protection against the development of type 2 diabetes (and with its management).

See also: Too Much Sitting Is Hazardous to Your Health

Reflections on Sedentary Behavior

Standardization of terms and methods by the scientific community will expand our capacity to understand and battle sedentary behavior. From the movement perspective, the evidence visibly shows that, to promote an optimal way of life for our clients, fitness pros should continue to develop and teach time-efficient daily exercise (aerobic and resistance training) programs.

We also need to develop new, imaginative interventions to combat sustained periods of sitting. Fitness pros can lead the way by developing creative “end-of-sitting” campaigns and contests to bring more awareness to our clients and fellow citizens that, yes, exercise is wonderful for health, but so is getting up and moving while at work and at home.

10 Quick Ways to Disrupt Sustained Sitting

- Get up and move after reading 4, 6 or 8 pages.

- Stand and move every time you change television channels.

- Do a few heel raises while loading or emptying the dishwasher.

- Take a brief walking break after each meal or snack.

- Each time you drink water, take a movement break as well.

- Instead of emailing colleagues at work, walk to their workspace and speak to them.

- Every 30 minutes, get up from sitting and move for 3 minutes.

- Try brief exercise bouts at home or at work. For example, do 10 partial squats followed by 20 alternating knee lifts.

- When the phone rings, answer and keep moving during your conversation.

- Stand and move every time you check your mobile device for text messages.

See also: The Office Worker’s Workout

References

Bellettier, J., et al. 2019. Sedentary behavior and prevalent diabetes in 6,166 older women: The Objective Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health Study. Journals of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 74 (3), 387–95.

Júdice, P.B., et al. 2016. What is the metabolic and energy cost of sitting, standing and sit/stand transitions? European Journal of Applied Physiology, 116, 263–73.

SBRN (Sedentary Behaviour Research Network). 2017. Accessed Apr. 15, 2019: sedentarybehaviour.org/.

Tremblay, M.S., et al. 2017. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN)—Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14 (75).

Len Kravitz, PhD

Len Kravitz, PhD is a professor and program coordinator of exercise science at the University of New Mexico where he recently received the Presidential Award of Distinction and the Outstanding Teacher of the Year award. In addition to being a 2016 inductee into the National Fitness Hall of Fame, Dr. Kravitz was awarded the Fitness Educator of the Year by the American Council on Exercise. Just recently, ACSM honored him with writing the 'Paper of the Year' for the ACSM Health and Fitness Journal.