Exercise and the Autism Population

Careful preparation and specific strategies can help trainers succeed with autistic athletes.

There are many misconceptions around exercise for those with autism. There can be profound cognitive challenges, and some do not adapt easily to exercise regimens. But, for many on the autism spectrum, a carefully structured program and a patient, well-prepared trainer can help them become healthier and more fit.

The population diagnosed with autism continues to grow and, therefore, the need for exercise programming. In 2021, the CDC reported that approximately 1 in 44 children in the U.S. is diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (Autism Speaks 2022). That means there’s a good chance that fitness professionals working with young people will eventually work with one who has autism.

Editor’s note: Check out this Member Spotlight to meet a fellow fit pro whose son was diagnosed with autism.

Autism: An Introduction

Symptoms

Autism is a neurobiological disorder (not a disease). According to the Autism Speaks (2022), the two cores symptoms are

- social communication challenges and

- restricted, repetitive behaviors.

Autism is also associated with high rates of certain physical and mental health conditions. These include the following:

- social communication challenges

- difficulty with verbal and non-verbal communication

- social challenges that can include difficulty with recognizing emotions and intentions in others, recognizing and expressing one’s own emotions, taking turns in conversation, and gauging personal space (appropriate distance between people)

- restricted and repetitive behaviors

Autism appears to result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors that disrupt normal development and often cause regression in emerging social and communication skills (Autism Speaks 2022). Note that vaccines have no causal link to autism; this has been researched exhaustively by numerous independent organizations in the United States, Canada, Sweden and Japan.

Motor Issues

Gross motor issues connected with autism can include low muscle tone/strength, poor stability, low strength endurance, compensatory movement patterning and poor gait (Staples & Reid 2010). These issues seem to occur prevalently in the autism spectrum disorder population as a result of several factors, including

- deficits in neural firing when performing movement,

- lack of exploratory play during infancy and the toddler years,

- lack of vigorous physical play in childhood and adolescence, and

- poor access to appropriate and ongoing physical fitness programs.

The last point is one where our professional expertise can bear fruit. As numerous studies, anecdotal reports and extensive media coverage have shown, young people are at high risk for lifestyle-related medical complications and diseases—including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity and some types of cancer. The ASD population is just as susceptible, and these young people may be even more so because of the lack of appropriate and available fitness programming (Curtin et al. 2009).

See also: Exercise Needed for Children’s Mental Health

Exercise and Autism

For fitness professionals who are serving this group, the most daunting task is to provide individualized programming that addresses the adaptive and cognitive deficits related to autism. Athletes with autism require specific adjustments to the movement screens we use to assess baseline physical functioning. These clients will often lack certain adaptive (self-regulation) and cognitive abilities typically required to start a fitness program. What we have to do is establish a hierarchy of goals springing from a simple question: “Where do I start?”

See also: Getting to the Heart of Pre-Exercise Screening

Adaptive Functioning

To realize fitness goals for people with autism, we need to make adaptive functioning the top priority. The first step is to assess and encourage motivation: As we all know, motivation keeps athletes engaged and focused; further, it ensures that they apply ample time under instruction to master exercises and activities, and that they seek enough exposure to physical activity to promote a training effect. Unfortunately, many people with autism simply do not have the motivation to perform a given (or any) physical activity, game or exercise.

These athletes may engage in “escape” or “avoidance” behaviors, such as wandering away; in more extreme cases they can become self-injurious or aggressive. In the latter situation, it is imperative that fitness professionals speak with the person’s behavior therapist to learn the right behavior protocols.

The Premack Principle

So, how does a fitness practitioner working with an ASD athlete establish motivation for performing a physical activity? Try using the Premack Principle (“If you do this, then you can have that”) to provide a “secondary reinforcer.” In other words, consider establishing a reward for performing the exercise(s). This might be access to a preferred activity (a break from exercise, listening to music, walking around, etc.). Rewards increase the likelihood that the athlete will perform the activity again (Mancil & Pearl 2008). One of the most compelling and beneficial aspects of using the Premack Principle is that fitness activities can eventually become reinforcing themselves, calling for fewer secondary reinforcers.

Where to Focus Your Efforts

What do people with autism need from a physical standpoint? Just like other populations, they need strength and stability in pushing, pulling, squatting and rotation. Locomotion (getting from point A to point B) is important for gait patterning, movement sequencing (motor planning) and strength endurance. Activity selection should emphasize developing foundational movement skills. Once a person can perform essential complex movement patterns—including biomechanically correct squatting, pressing and pulling (in multiple planes)—an instructor can progress activities in a variety of ways. You can add

- resistance by increasing the weight of the object(s) or changing the leverage

- repetitions to the movement/exercise

- time to the movement/exercise

- additional movement

Adding resistance improves muscle strength and boosts physical abilities in the daily lives of people with autism. Existing deficits and potential limitations due to adaptive abilities (less on-task behavior) make it much more time-consuming for these athletes to develop strong, stable multijoint movement patterns compared with people who have typical development patterns.

Regressions and Progressions

Some exercises may require regression rather than progression.

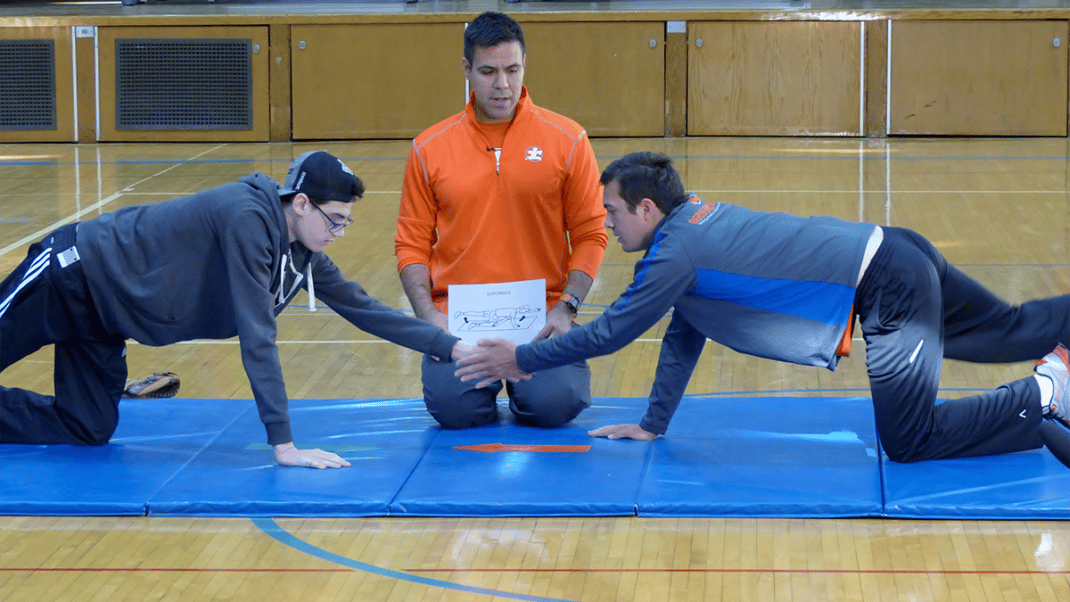

Exercise regressions simplify, or “break down,” complex movement patterns that are too difficult for ASD athletes. Regressing a movement may include using a physical prompt (guiding the athlete through the movement to ensure proper technique) or providing a less challenging variation. Using a soft medicine ball with a large (10- to 12-inch) diameter for squats is an excellent way to teach “sitting” into the movement. It provides the athlete both a visual cue and proprioceptive feedback from sitting (briefly) on the ball.

Below is a complex movement regressed into its component movements. You can start at the athlete’s base level of performance and work your way up to the final movement in steps:

Medicine Ball Push-Throw

Step/Goal:

1. Push-throw with nonweighted ball from 3 feet away.

2. Push-throw with nonweighted ball from 5 feet away.

3. Push-throw with nonweighted ball from 10 feet away.

4. Push-throw with 2-pound medicine ball from 3 feet away.

5. Push-throw with 2-pound medicine ball from 5 feet away.

6. Push-throw with 2-pound medicine ball from 10 feet away.

7. Squat, and then push-throw with 2-pound medicine ball from 10 feet away.

In the first few goals, the athlete is learning the movement pattern and, likely, is overcoming deficits in upper-body strength (vertical push). By step 5, the activity has become more dynamic, with a heavier ball and an increase in the distance between partners. Physical goals typically will not progress in perfectly linear fashion. The athlete may increase push-throw distance from 5 feet to 8 feet in three sessions, and then plateau for 2 months before adding 2 feet of distance.

Also, as is typical of adolescent and teen populations, growth spurts and structural changes can be both a benefit and a temporary hindrance to performance.

Autism and Cognitive Abilities

Those on the autism spectrum may have difficulty following multistep verbal directions. An instruction like “Go over and pick up the small sandbag, slam it on the floor five times, then run around the cones” may be too much information to process. Cognitive abilities are not necessarily measured by comparisons like “low” or “high”; the key is to determine how best an individual learns. Does a particular athlete respond better to visual cues (having you demonstrate the exercise) or kinesthetic cues (being physically guided)? Depending on the exercise or activity, a combination of kinesthetic and visual cues may work best.

Provided the athlete is accepting your directions, demonstrate the movement slowly, and follow by guiding the learner through the movement. This ensures that the person experiences early success and does not repeatedly perform the movement incorrectly. Having to constantly correct the activity frustrates the athlete and the instructor. It leads to a problematic feedback loop of “No, not that way. Do it this way,” or to similar situations where the expectation becomes unclear and the annoyance factor escalates.

Matching your instruction to the athlete’s learning style and pace alleviates anxiety and disappointment. Because many young people on the autism spectrum are averse to structured physical activity, using cues (short verbal directions, demonstration of the exercise, and/or physical prompts) and teaching methods (starting at baseline abilities, then regressing and/or progressing the activities) accomplishes much more in less time with fewer unnecessary challenges. Figure 1 condenses the three areas of ability into conceptual/practical actions.

Condensing the Density With Exercise and Autism

Providing exercise programming for the autism population may require more planning and more consideration of aspects of human ability that are usually insignificant, or less significant, in achieving client goals. Still, it is our responsibility as an industry to provide fitness as a gateway toward better performance and life enhancement for all populations. The autism community should be no exception.

Client’s Three Areas of Ability

Physical

- Assess baseline skills with complex, multijoint movements.

- Progress/Regress individual exercises as needed.

- Following independent mastery, progress the exercise/activity using one or more of the four progression variables listed in the “Where to Focus Your Efforts” section of this article.

Adaptive

- Assess client’s motivation to perform physical activity in general, and to perform certain exercises specifically.

- Implement secondary reinforcers as needed (breaks, access to a preferred activity).

- Begin to “fade” secondary reinforcers (for example, by taking five extended breaks during the session rather than 10). Continue providing behavior-specific praise/feedback.

Cognitive

- Assess client’s ability to follow one-step and, if applicable, two- and three-step directions.

- Deliver instructions in short verbal cues (no more than four words), demonstrate exercises and use physical prompts where applicable.

- Aim to master contingency between directions and activity. (For example, the instructor says, “Do an overhead throw,” and the athlete performs it correctly.) Include or increase two- and three-step activities in programming.

Each of the three areas of ability has a progressive nature. Below are the stages of each area, beginning with the most challenging and moving toward the most optimal.

Physical Progression

1. shows significant motor and strength deficits

2. displays emerging strength/stability/range of motion in major movement patterns

3. masters basic exercises (push, pull, squat, locomotion, rotation) independently

4. masters basic exercises with increased resistance independently

5. adds movement patterns to mastered exercises/activities (example: squats, then performs overhead press with sandbag)

As noted earlier, not all movements and activities will progress in a linear fashion. This is a general model to follow. The athlete may perform some skills better than others, and progress may be slower or faster depending on baseline physical and adaptive skills in a specific exercise or movement.

Adaptive Progression

1. shows significant maladaptive behaviors (avoiding instructions or activity)

2. shows tolerance/compliance with select activities

3. is able to comply with most activities, when secondary reinforcement is provided

4. graduates to fewer secondary reinforcers or less break time

5. is motivated to perform exercise activities without secondary reinforcement

6. is motivated to create new activities/creative play and to engage in physical activity independently

Cognitive Progression

1. requires a full physical prompt to perform most activities at baseline ability level

2. can perform some exercises when given a combination of visual and slight physical prompts

3. can perform some activities with only a visual prompt

4. attains mastery of several directions (can follow verbal direction, such as “Squat to the ball,” “Do rope swings” or “Press overhead”)

5. can perform numerous one-step activities based on verbal direction (or pictures of activities, if using a picture-based communication system)

6. can perform several two- and three-step activities

Some individuals may not progress to following two- and three-step activities based on verbal direction. Increasing this skill is not a high priority, as increasing adaptive and physical abilities should be the focus of any fitness program for the ASD population.

Autism Facts

- One in 88 children is diagnosed on the autism spectrum.

- Autism is a neurobiological disorder with several suspected environmental and genetic causes.

- Behavioral, cognitive and gross motor deficits are common among those with autism.

- Individuals with ASD have limited access to appropriate fitness programming.

Areas of Ability

- Physical, adaptive and cognitive abilities must be accounted for.

- Understanding these variables will guide goal-setting instructional style—and behavior support.

- Exercises and activities that the athlete has not yet mastered should be broken down or regressed to simpler versions.

Physical, Adaptive and Cognitive Strategies

Physical. Figure out which movements or exercises the athlete can and cannot do. Focus

on program development and fitness goal setting.

Adaptive. Assess the athlete’s motivation to perform fitness activities and specific movements. Develop a plan for behavior support and reinforcement.

Cognitive. Focus on learning style (visual and/or kinesthetic); develop an appropriate teaching method.

References

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2013. www2.aap.org/immunization/families/autismfacts.html; retrieved June 1, 2013.

Autism Society. 2013. www.autism-society.org/about-autism; retrieved June 1, 2013.

Autism Speaks. 2022. Autism statistics and facts. Accessed Apr. 7, 2022: autismspeaks.org.

Curtin, C., et al. 2009. The prevalence of obesity in children with autism: A secondary data analysis using nationally representative data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. BMC Pediatrics, 10 (11). www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/10/11/

Mancil, G.R., & Pearl, C.E. 2008. Restricted interests as motivators: Improving academic engagement and outcomes of children on the autism spectrum. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 4 (6), 1-15. http://journals.cec.sped.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1554&context=tecplus

Staples, K.L., & Reid, G. 2010. Fundamental movement skills and autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40 (2), 209-17.

Eric Chessen, MS

Eric Chessen, MS, is the founder of Autism Fitness. He is an exercise physiologist with an extensive educational and clinical background in applied behavior analysis. He has spent over a decade developing and implementing successful individual and group exercise programs in a variety of settings. More information can be found at www.autismfitness.com and www.strongerthanu.com