Shoulder the Load: Mechanics and Programming for Shoulders

Understand basic shoulder mechanics and learn how to program a routine that will enhance your clients’ performance and durability.

We tend to take bodily functions for granted until something goes awry. This is certainly true of shoulder function. Rarely do we give our shoulders a second thought until we feel a sharp twinge when reaching overhead or a radiating ache that keeps us awake at night. And yet, “shoulder pain is a common and disabling complaint. Recovery . . . can be slow, with recurrence rates at 25%” (Cadogan et al. 2011).

Pain in the shoulder not only affects function; it can also limit ability to perform many upper-body exercises, which may discourage your clients and even cause them to give up. Personal trainers don’t have the credentials to diagnose and treat shoulder pain (always leave those steps to doctors and physical therapists), but with the right education, trainers can create a preventive exercise program.

In an attempt to strengthen the shoulders, however, some trainers opt for traditional upper-body exercises that strengthen the large muscle groups around the shoulders, while neglecting the smaller, equally important ones involved in shoulder stability, health and function. For instance, researchers call out the danger of strengthening the deltoids in isolation, as this leads to superior migration of the humeral head, thus increasing the chances of subacromial impingement (Reinold, Escamilla & Wilk 2009).

This article reviews the anatomy and function of the glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints and provides basic, low-risk exercises that are designed to improve rotator cuff strength, shoulder mobility and scapulohumeral rhythm.

Shoulder Anatomy

Review the main muscles and actions of the shoulder to ensure you understand foundational concepts before designing a program.

The Rotator Cuff

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that originate on the scapula and insert at the humerus. Here are the four rotator cuff muscles and their actions:

- subscapularis: internally rotates the shoulder joint and stabilizes the humeral head in the glenoid fossa

- supraspinatus: abducts the shoulder joint and stabilizes the humeral head in the glenoid fossa

- infraspinatus: externally rotates the shoulder joint and stabilizes the humeral head in the glenoid fossa

- teres minor: externally rotates the shoulder joint and stabilizes the humeral head in the glenoid fossa

Source: Kendall et al. 2005.

Although the rotator cuff muscles all have different functions, they also have a common one: stabilization of the humeral head, often called “centration.” This is critical for maximal power transfer and for reducing the risk of joint pathology, such as impingement or joint laxity.

Reinold, Escamilla & Wilk say, “Appropriate rehabilitation progression and strengthening of the rotator cuff muscles are important to provide appropriate force to help elevate and move the arm, compress and center the humeral head within the glenoid fossa during shoulder movements (providing dynamic stability), and provide a counterforce to humeral head superior translation resulting from deltoid activity (minimizing subacromial impingement).”

Thus, rotator cuff strength and proper activation are critical in shoulder health and maintenance.

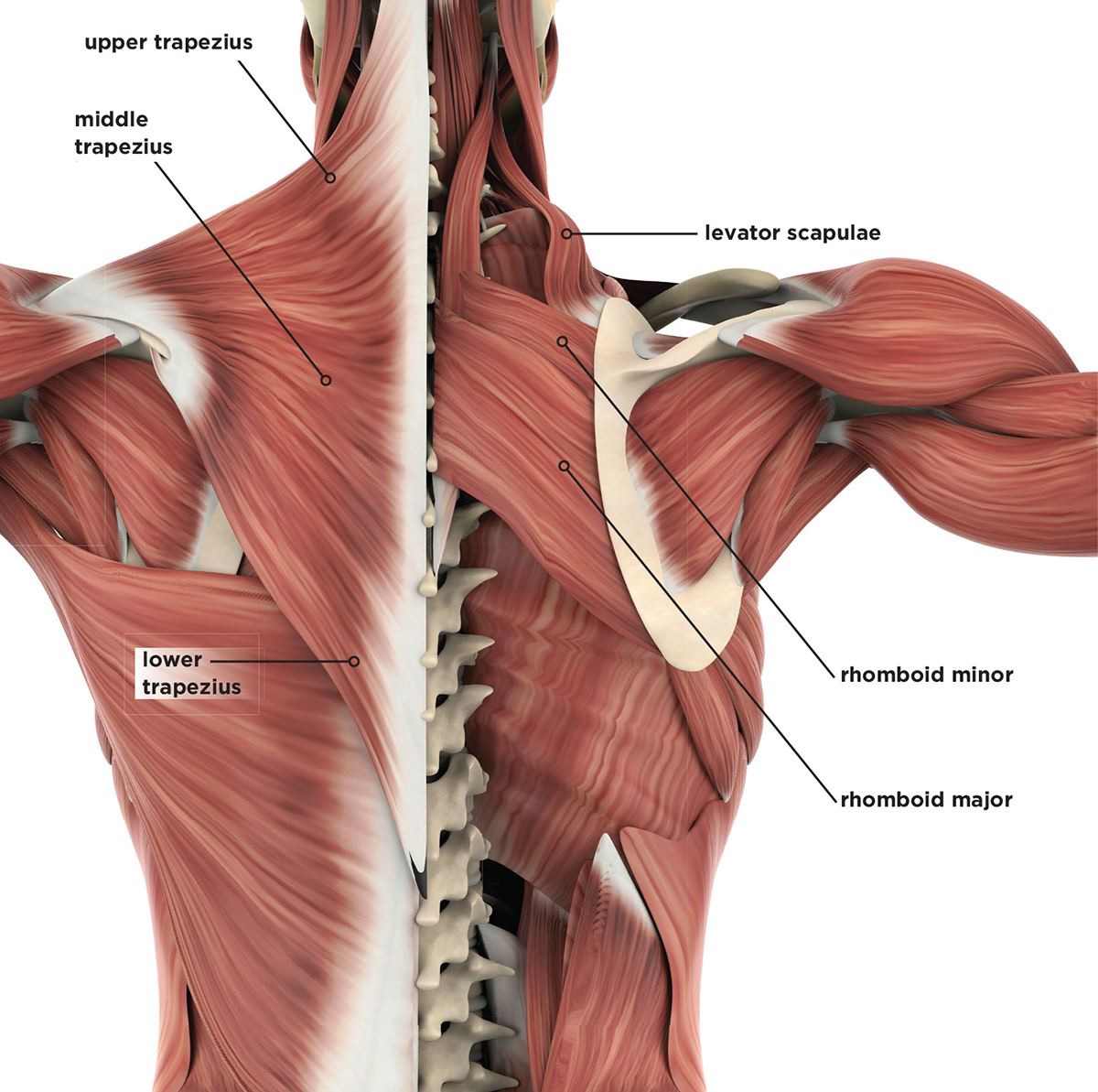

Scapulothoracic Muscles

While the rotator cuff is crucially important to shoulder function, so is the scapulothoracic musculature, which works in concert to smoothly and efficiently move the shoulder in all three planes of motion, making humans surprisingly agile through the upper extremities. The primary muscles that control scapular movements include the upper and lower trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids, and pectoralis minor (Reinold, Escamilla & Wilk 2009). Following is a brief review of scapular muscle actions:

- upper trapezius and lower trapezius: upper fibers elevate the scapula and lower fibers depress and posteriorly tilt it—when working together, they upwardly rotate the scapula for overhead motion

- serratus anterior: abducts and upwardly rotates the scapula

- rhomboids: adduct, elevate and downwardly rotate the scapula

- pectoralis minor: anteriorly tilts and downwardly rotates the scapula

Source: Kendall et al. 2005.

Working in Harmony

A force couple is a system of forces that work synergistically to generate rotation. One example of this occurs in the scapulothoracic joint, where the upper trapezius, lower trapezius and serratus anterior work in harmony to upwardly rotate the scapula, allowing for overhead shoulder motion. Maintaining appropriate scapular muscle strength and balance allows the scapula and humerus to move in coordination during arm elevation. That relationship is known as the scapulohumeral rhythm.

“During humeral elevation,” say Reinold, Escamilla & Wilk, “the scapula upwardly rotates in the frontal plane, rotating approximately 1° for every 2° of humeral elevation until reaching 120° humeral elevation, and thereafter rotates approximately 1° for every 1° humeral elevation until maximal arm elevation, achieving at least 45° to 55° of upward rotation. During humeral elevation, in addition to scapular upward rotation, the scapula also normally tilts posteriorly approximately 20° to 40° in the sagittal plane and externally rotates approximately 15° to 35° in the transverse plane.”

In simple terms, when the arm moves up, the scapula has to move with it and also tilt back in a coordinated effort. Individuals with altered scapula mechanics often suffer from—or are predisposed to—shoulder pathology. “During arm elevation in the scapular plane, individuals with subacromial impingement exhibit decreased scapular upward rotation, increased scapular IR (winging) and anterior tilt, and decreased subacromial space width, compared to those without subacromial impingement,” explain Reinold, Escamilla & Wilk. “Altered scapular muscle activity is commonly associated with impingement syndrome.” Based on this research, it is important to incorporate exercises that address scapular winging, lack of upward rotation and excessive anterior tilt.

Enhanced Injury Prevention

The rotator cuff musculature is critical in internal rotation, external rotation, elevation and humeral joint centration. The muscles surrounding the scapula also play a critical role in arm motion and, if not functioning properly, can lead to shoulder dysfunction and pathology. By understanding rotator cuff and scapulothoracic anatomy and function, and by implementing a basic program (see “Strengthening the Rotator Cuff: Five Moves,” below), you will directly enhance your clients’ chances of preventing shoulder injuries while improving overall function.

Stretch It Out: Prepare for Movement

Perform the following stretches prior to taking clients through the strengthening routine.

Posterior Shoulder Stretch

- Grab upper arm with opposite hand and pull across chest horizontally until you feel stretch in back of shoulder.

- Hold 15–30 seconds.

- Repeat, opposite side.

Foam Roller Opener/Thoracic Extension

- Lie perpendicular, midback on foamroller, fingers crossed behind head.

- Roll up and down midback while simultaneously stretching into extension.

- Perform for 1 minute, pausing on any areas of excessive tightness.

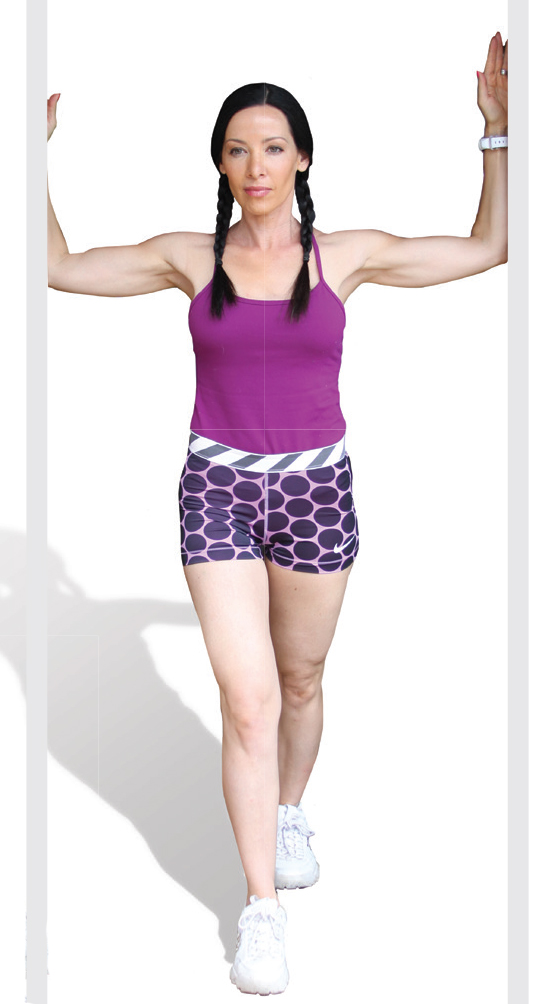

Doorway Stretch

- Place forearms on either side of door jamb, elbows at 90 degrees.

- Stand in split stance and step into doorway, stretching anterior chest and shoulders; brace core.

- Hold for 30 seconds; switch which leg is forward and repeat another 30 seconds.

Strengthening the Rotator Cuff: Five Moves

This exercise series addresses rotator cuff strength, scapular strength and scapulohumeral rhythm. I highly recommend taking your clients through the “Stretch It Out” series (above) before doing this workout. Mobilizing the shoulders and thoracic spine will increase the ease and effectiveness of the strength training exercises and minimize any risk of injury.

These exercises are intended to give your clients a “jump-start” on strengthening the shoulders and enhancing overall function. A client who achieves proficiency with these moves can try performing them on an unstable surface (e.g., a stability ball for the prone Y) or modifying the stance (e.g., using a split stance for the sword draw).

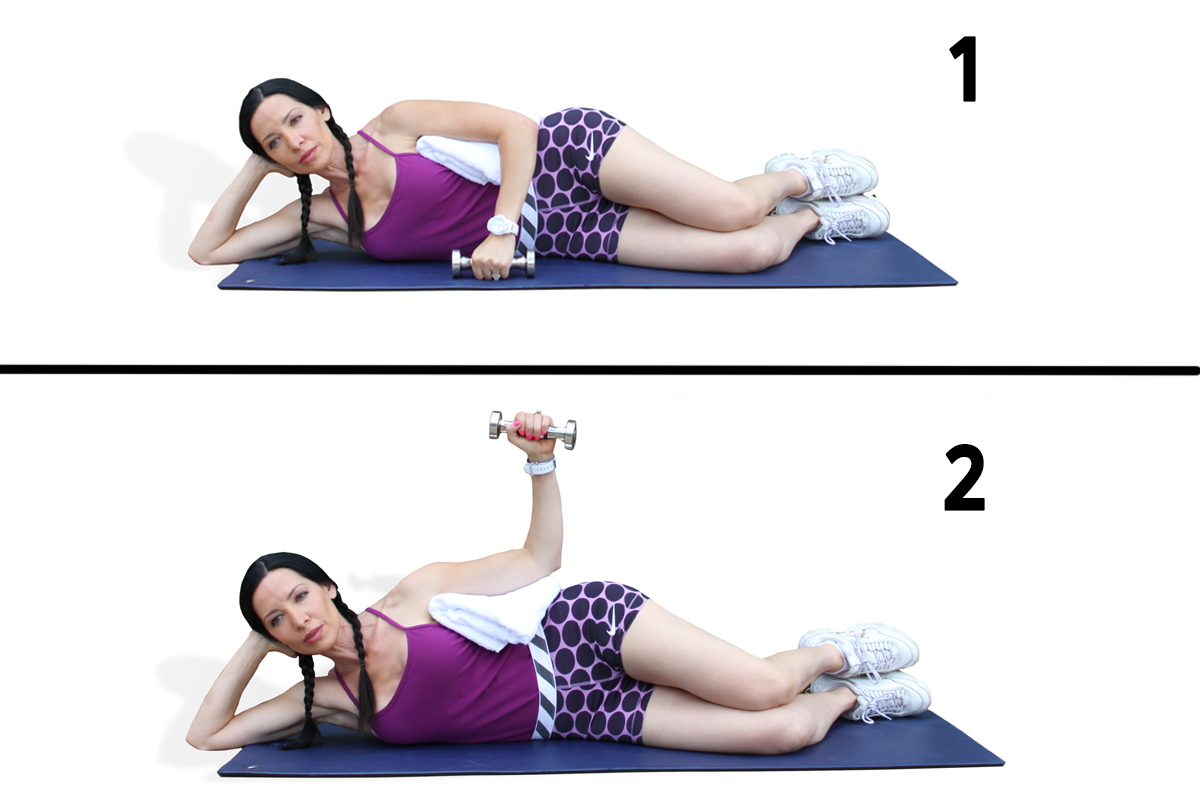

1. Sidelying External Rotation

Let’s first look at an exercise designed to maximally strengthen

the external rotators, which centrate the humeral head and also decelerate the arm during overhead-motion follow-throughs (e.g., in a tennis serve or a baseball pitch). Reinold and colleagues analyzed several commonly used exercises to determine which one was most effective at strengthening the external rotators. Shoulder external rotation in a sidelying position was found to elicit the strongest EMG signal for the infraspinatus and teres minor combined (Reinold et al. 2004).

- Lie sideways, knees bent, on bench or mat.

- Place rolled-up hand towel between humerus and rib cage.

- Maintain 90-degree angle between upper and lower arm while rotating arm upward toward ceiling.

- Ensure there is no hip or spinal movement during external rotation.

- Do 1–2 sets of 10–12 repetitions; this should sufficiently activate the external rotators and build capacity in the posterior cuff.

2. Prone Y (Full Can)

The “empty can” move strengthens the supraspinatus and is a cross between a front raise and a lateral raise with thumb pointed down. However, some researchers have found that this exercise heavily recruits both the medial and anterior deltoids, causing superior translation of the humeral head and potentially leading to impingement.

By contrast, “[an exercise] such as the prone full can, which generates high levels of rotator cuff and posterior deltoid activity, may be both safe and effective for rotator cuff strengthening,” according to Reinold, Escamilla & Wilk (2009). Additionally, Ekstrom, Donatelli & Soderberg (2003) found that the greatest EMG signal amplitude for the lower trapezius occurred during the prone full can, which not only strengthens the supraspinatus but also activates the lower trapezius, external rotators and rhomboids.

This exercise can be performed with both arms simultaneously and is

commonly referred to as a “prone Y.”

- Lie prone on bench, holding light weights or no weights.

- Elevate arms toward ceiling while maintaining straight elbows, thumbs up.

- Perform 1–2 sets of 10–12 repetitions.

3. Wall Slide

Researchers recently found that the wall slide exercise may be effective at reducing pain and improving scapular alignment in subjects with downward scapular rotation (Kim & Lim 2016). Interestingly, physical therapists (including myself) have been using the wall slide for years to address rhomboid and serratus anterior strength and overhead shoulder mechanics. Born from the work of Shirley Sahrmann, PhD, PT, FAPTA, and outlined in her book Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Systems Impairment (Mosby 2002), the wall slide is considered to be a gold-standard shoulder exercise and is effective at reducing pain and improving scapular alignment.

- Stand with back against wall, feet approximately 1 foot away from base.

- Place elbows against wall, bent at 90 degrees, wrists on wall, or as close as possible.

- Brace core and flatten back against wall to reduce rib-flare.

- Slowly raise arms overhead into diagonal finish position.

- Perform 1–2 sets of 10–12 repetitions.

4. Pushup With a Plus

As previously discussed, the serratus anterior is an important scapulothoracic muscle that helps to stabilize and upwardly rotate the scapula. Decker et al. (1999) compared several common exercises designed to recruit the serratus anterior. The three exercises that produced the greatest EMG signal in the serratus anterior were pushup with a plus, dynamic hug and punches.

Let’s look at pushup with a plus:

- Assume pushup or modified pushup position.

- Check for braced core and neutral spine.

- Descend toward floor while maintaining ear, shoulder and hip alignment.

- Press upward, but instead of stopping at normal top position, keep pressing up until scapulae protract forward on rib cage (the “plus”).

- Perform 1–2 sets of 10–12 repetitions.

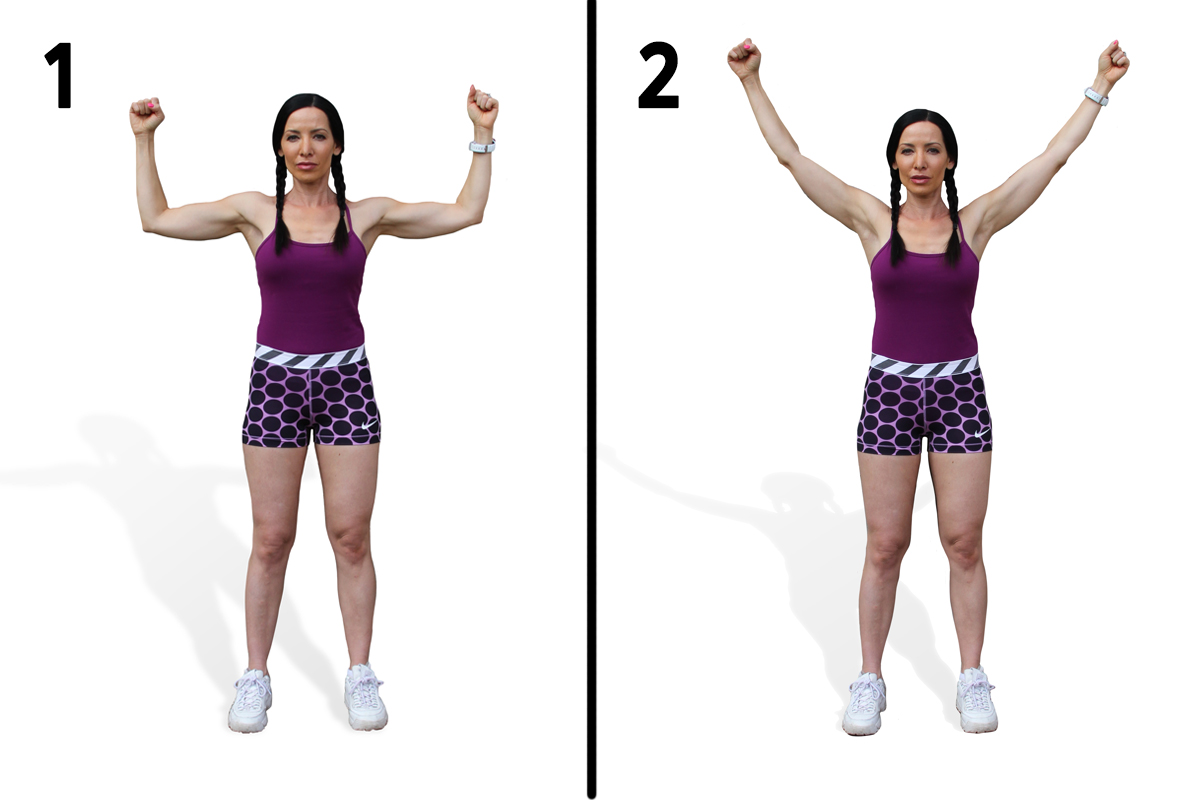

5. Sword Draw

The final exercise in this series challenges the rotator cuff and scapulothoracic muscles in a dynamic, functional and safe movement pattern. The sword draw, which involves flexion, abduction and external rotation, is based on a proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) pattern commonly used by physical therapists to restore shoulder function.

- Stand with one foot on resistance cord and other end of cord in opposite hand.

- Move arm into simultaneous shoulder flexion, abduction and external rotation, similar to drawing a sword from its sheath. This exercise can also be performed with a dumbbell.

- Perform 1–2 sets of 10–12 repetitions.

References

Cadogan, A., et al. 2011. A prospective study of shoulder pain in primary care: Prevalence of imaged pathology and response to guided diagnostic blocks. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 12 (119).

Decker, M.J., et al. 1999. Serratus anterior muscle activity during selected rehabilitation exercises. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 27 (6), 784–91.

Ekstrom, R.A., Donatelli, R.A., & Soderberg, G.L. 2003. Surface electromyographic analysis of exercises for the trapezius and serratus anterior muscles. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 33 (5), 247–58.

Kendall, F.P., et al. 2005. Muscles: Testing and Function with Posture and Pain. Baltimore: Lippencott Williams and Wilkins.

Kim, T.H., & Lim, J.Y. 2016. The effects of wall slide and sling slide exercises on scapular alignment and pain in subjects with downward rotation. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 28 (9), 2666–69.

Reinold, M.M., et al. 2004. Electromyographic analysis of the rotator cuff and deltoid musculature during common shoulder external rotation exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 34 (7), 385–94.

Reinold, M.M., Escamilla, R., & Wilk, K.E. 2009. Current concepts in the scientific and rationale behind exercises for glenohumeral and scapulothoracic musculature. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 39 (2), 105–17.

Sahrmann, S. 2002. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis: Mosby.

Pete Holman, MSPT

Pete Holman, MSPT, is a physical therapist, certified strength & conditioning specialist and US National taekwondo champion and team captain. His passion for health and fitness has stimulated a successful adjunct career as an inventor. He produced several products, most notably the TRX® Rip Trainer and the Nautilus Glute Drive. Specializing in biomechanics, core performance and the aging athlete, Pete uses his experience as an elite level athlete and his unique knowledge of the human body, to bring out the athlete in us all. Pete is an active contributor to PTontheNet, IDEA Fitness Journal, STACK Magazine and IronMan Magazine.