Stress is a widespread, growing health crisis across much of the world. The COVID-19 pandemic has seriously affected the mental and physical health of many clients, disrupting work, healthcare services, classroom learning for students (of all ages), the economy and relationships (see “Stress in America,” below). We all intuitively understand the impact of stress on mental health, but stress physiology is just as deleterious.

Here, we’ll examine how stress affects the functioning of our bodies and take solace in opportunities that fitness professionals have to counteract this global crisis—one client at a time.

The Basics: Acute and Chronic Stress Physiology

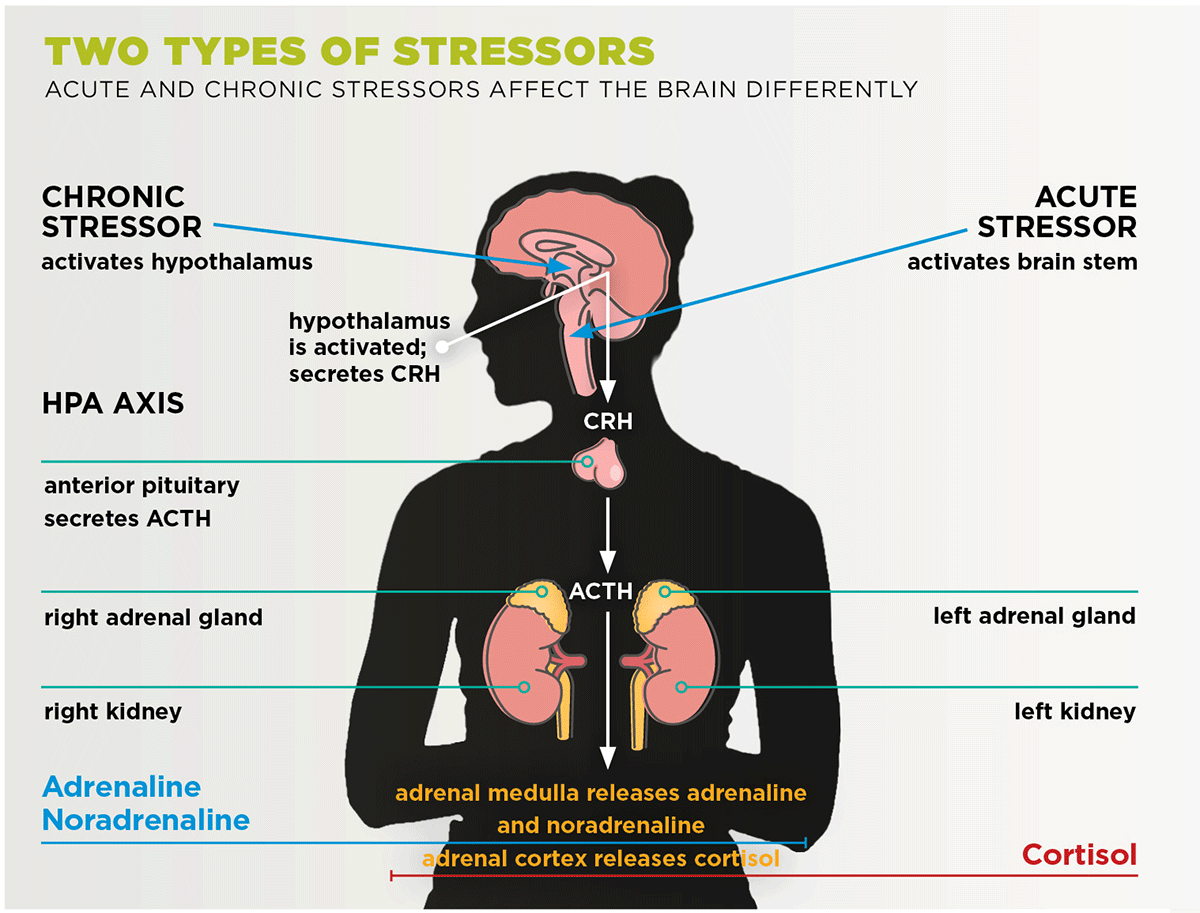

According to Gulzhaina et al. (2018), stress is the process by which a person reacts when faced with internal or external challenges and problems. Rohleder (2019) synthesizes several studies indicating that, in most cases, acute (short-term) stressors are beneficial for immediate survival. With acute stressors, a person often experiences the alarm reaction known as the fight-or-flight response, in which the body mobilizes hormonal resources (adrenaline and noradrenaline) (see “Two Types of Stressors,” right) (Anghelescu et al. 2018). Harkness & Monroe (2016) add that acute life stressors can vary in severity or level of perceived threat.

Chronic (long-term) stressors are ongoing and enduring in nature and therefore distinct from acute life events (Harkness & Monroe 2016). Chronic stressors are also different physiologically (see page 13). Examples of chronic stressors, which vary in severity, include dealing with an unending illness or prolonged financial difficulties.

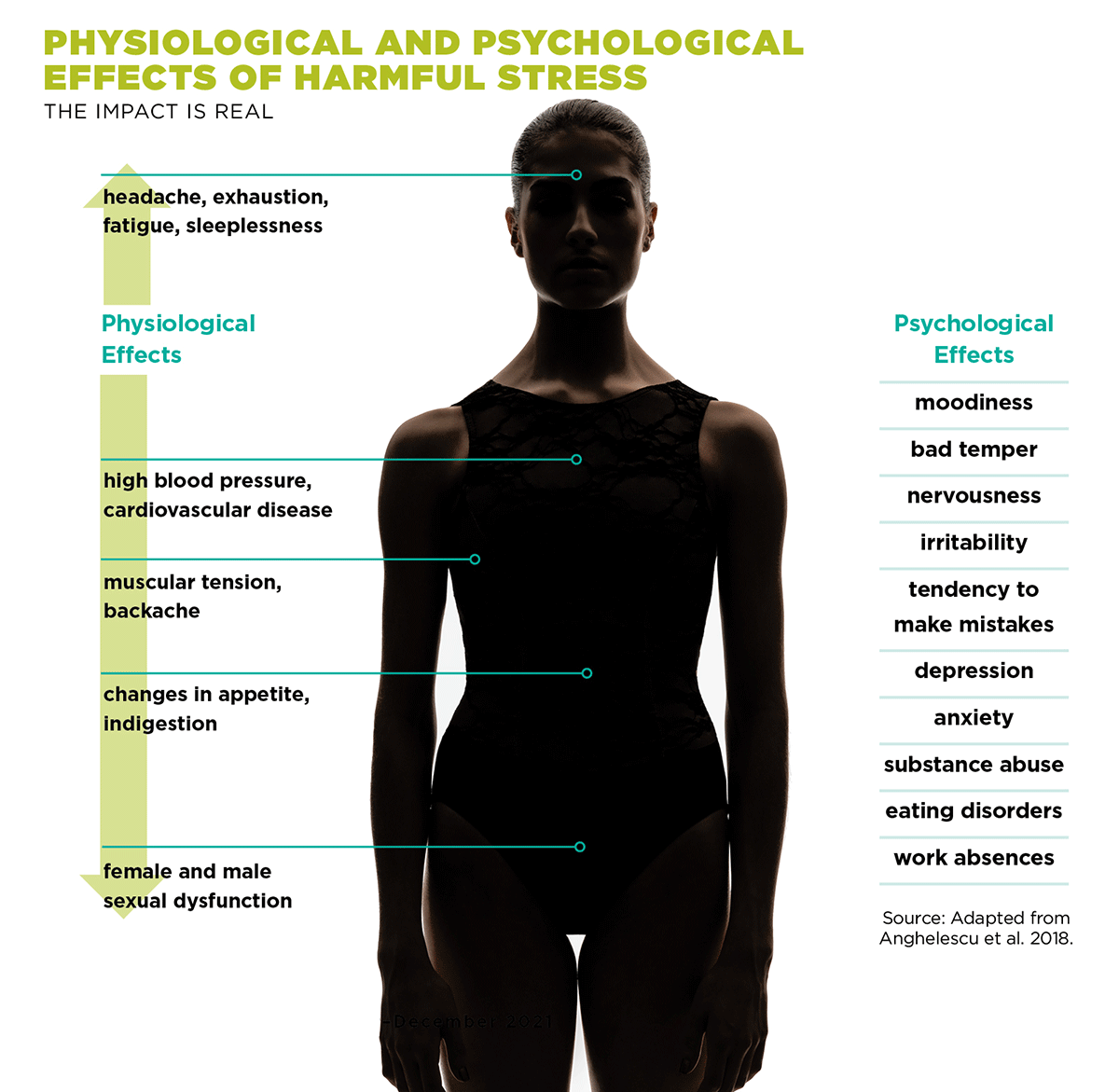

Rohleder (2019) summarizes evidence denoting that chronic stressors are associated with a large range of diseases, including cancer, insulin insensitivity and cardiovascular disease, as well as psychological stress responses (e.g., anger and anxiety) (see “Physiological and Psychological Effects of Harmful Stress,” below).

See also: Turn Up Mindful Exercise to Turn Down Stress

Stress Physiology: How Stress Impacts Physical Health

Memory and Emotion Processing

In a recent review, Lupien and colleagues (2018) explain that enduring chronic stressors can contribute to the development (or continuance) of health problems due to elevated levels of glucocorticoid hormones, particularly cortisol. When cortisol levels are high, they can directly access and influence cognitive processes in the brain, leading to impairments in attention, memory and emotion processing.

Areas of the brain affected by elevated cortisol are the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus and the amygdala. Lupien et al. state that these three brain structures play a crucial role in whether a situation is interpreted as stressful or not and in the subsequent selection or inhibition of possible responses. The researchers also note that chronic elevated production of glucocorticoids is highly associated with the development of depressive disorders.

Heart Disease

Chronic stress heightens the risk for multiple types of cardiovascular disease (Song et al. 2019). Until recently, however, the mechanism by which stress translates to cardiovascular disease was unknown.

In a landmark study by Tawakol et al. (2017), the researchers showed (for the first time) that there is a definite mechanism linking cardiovascular events with resting metabolic activity within the amygdala (in the brain)—preceded and brought about by arterial inflammation.

A Toolbox for Helping Clients Manage Stress

It is important for fitness pros to share with clients that stress and stress physiology are a reality of everyday life (Gulzhaina et al. 2018). Stress management interventions use mind-to-body and body-to-mind strategies (see “How Exercise Combats Stress,” below) to reduce the effects of chronic stress (Fish 2018). Interestingly, for clients who enjoy taking yoga classes, a recent study showed that practicing yoga at the local gym twice a week effectively improves psychological health for the general working public (Maddux, Daukantaite & Tellhed 2018).

Here are four evidence-based stress management interventions that fit pros can teach clients:

Mindfulness meditation. Meditation is an intervention in which people sit comfortably for some minutes (20–40) and focus on their internal breathing. It has been shown to reduce stress, negative emotions, anxiety and depression and strengthen areas of the brain associated with relaxation and joy (Gulzhaina et al. 2018).

For mindfulness meditation, have the client laser-focus on the present moment, not dwelling on the past or trying to imagine the future. Encourage the client not to overanalyze, judge or overthink the stressful situation.

Diaphragmatic breathing. Diaphragmatic breathing (also known as abdominal or belly breathing) is an intervention that can reduce stress, lower high blood pressure (in hypertensive persons), and decrease anxiety and depression (Fish 2018). Fish points out that when clients become stressed, they often lift their shoulders to inhale and exhale and their breath becomes short and shallow. If this type of breathing persists, it may intensify the stress response (Fish 2018).

For diaphragmatic breathing, have clients perform slow, even, deep breathing through the nose for 5–10 minutes (progressing to 15–20 minutes), while engaging the diaphragm on the inhalation. When the diaphragm is engaged (i.e., it lowers into the abdominal cavity), the belly protrudes on the inhalation, and there is minimal shoulder and chest movement. Belly protrusion is easily observed by placing a hand on the abdomen.

Progressive muscle relaxation. Progressive muscle relaxation is another effective intervention for reducing stress and anxiety. The practice consists of consecutively tensing and relaxing muscles (Gulzhaina et al. 2018). Muscle groups to tense and relax can be the feet, legs, buttocks, abdomen, chest, shoulders, arms, hands, forehead and face.

In a sequential pattern (e.g., from feet to face), have clients close their eyes and purposely contract a muscle group (near maximally) for 10 seconds and then release the contraction for 20 seconds before going to the next muscle group. Repeat the contraction-relaxation cycle with all muscle groups. It helps to instruct clients to focus on the muscles contracting and relaxing, so people learn to distinguish between tension and relaxation in the muscles.

Progressive muscle relaxation has been shown to reduce cortisol levels, high blood pressure and headaches and to improve cardiac management of patients after bypass surgery (Gulzhaina et al. 2018).

Positive mental imagery. Mental imagery is recognized in research as an important intervention for mental health treatment of stress, anxiety and insomnia. Positive mental imagery, which entails imagining a nice place (for 5–15 minutes), is cost-effective and can readily be used at home. Visualizing beautiful scenes may also improve clients’ quality of life (Jerath et al. 2020).

Jerath et al. discuss re-search showing that envisaging natural environments (such as a forest) can reduce stress and help form a deep connection with nature. The researchers submit that targeting stress arousal when it’s time to sleep is optimal because it promotes relaxation.

See also: Coping Through Stress to Flourish

Conclusion: Stress Physiology

Fitness pros have an incredibly meaningful opportunity to help clients deal with mounting life stressors. The stress management strategies presented in this article are evidence-based and effective, require no specialized equipment, and are easy to introduce to clients. Begin the de-stressing now!

Acute Stressor: Activates the Autonomic Nervous System

The acute stressor activates the autonomic nervous system in the brain stem, which sends a message to the adrenal medulla to release the fight-or-flight hormones: adrenaline and noradrenaline.

Chronic Stressor: Activates the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis

- A chronic stressor activates the hypothalamus, which releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH); this in turn activates the pituitary gland.

- The pituitary gland releases adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), which activates the adrenal glands.

- The adrenal cortex releases glucocorticoids (GC). The dominant GC in humans is cortisol.

- The brain and most tissues in the body have cortisol receptors, which regulate immune function, reproduction, cardiovascular function, metabolism and cognition.

Source: Gulzhaina et al. 2018; Azuma et al. 2017; Anghelescu et al. 2018.

How Exercise Combats Stress

- Exercise provides a behavioral distraction from stressful situations.

- Physiological changes that occur with exercise may reduce a person’s sensitivity to chronic stress.

- Regular exercise has a preventive effect on several major diseases associated with elevated stress levels.

- Exercise stimulates the development of self-efficacy and mastery, which lessen negative stressors.

- Exercise has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression, which are associated with stress.

- For stress management through exercise, follow current recommendations: 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise per week.

10 Holiday Stress Coping Strategies

With the holidays often come new stressors for clients. Family get-togethers, shopping, decorating, gift buying and wrapping, cooking and baking, and attending special activities can place extra demands on clients and lead to stress.

Here are 10 holiday stress coping strategies from the Mayo Clinic (2020):

- Reach out. If you feel lonely or isolated, seek out religious or other social communities.

- Be realistic. Even though your holiday plans may look different because of the pandemic or other issues, you can find ways to celebrate.

- Acknowledge your feelings. It’s normal to feel a range of feelings—including sadness, grief and happiness—during the holidays.

- Take a break for yourself. Find an activity that clears your mind.

- Keep up your health habits. Eat healthy meals, get plenty of sleep, maintain your regular exercise routine and take a breather from technology.

- Be budget savvy. Decide how much money you can afford to spend on gifts and food, and stick to it.

- Plan ahead. Good planning helps to combat last-minute scrambling.

- Learn to say no. Friends and colleagues will understand if you can’t participate in every activity.

- Take control. Recognize your holiday triggers, such as financial pressures, so you can prevent them.

- Get help if you need it. If you feel persistently irritable, hopeless or sad and unable to face your daily routine, talk to a mental health professional.

References

Anghelescu, I-G., et al. 2018. Stress management and the role of Rhodiola rosea: A review. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 22 (4), 242–52.

APA (American Psychological Association). 2021. One year later, a new wave of pandemic health concerns. Accessed Aug.9, 2021: apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2021/one-year-pandemic-stress.

Azuma, K., et al. 2017. Association between mastication, the hippocampus, and the HPA axis: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18 1687.

Fish, M.T. 2018. Don’t stress about it: A primer on stress and applications for evidence-based stress management interventions in the recreational therapy setting. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 52 (4), 390–409.

Gulzhaina, K.K., et al. 2018. Stress management techniques for students. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 198, 47–56.

Harkness, K.L., & Monroe, S.M. 2016. The assessment and measurement of adult life stress: Basic premises, operational principles, and design requirements. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125 (5), 727–45.

Jackson, E.M. 2013. Stress relief: The role of exercise in stress management. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal, 17 (3), 14–19.

Jerath, R., et al. 2020. The therapeutic role of guided mental imagery in treating stress and insomnia: A neuropsychological perspective. Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 9 (1), 21–39.

Lupien, S.J., et al. 2018. The effects of chronic stress on the human brain: From neurotoxicity, to vulnerability, to opportunity. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 49, 91–105.

Maddux, R.E., Daukantaite, D., & Tellhed, U. 2018. The effects of yoga on stress and psychological health among employees: An 8- and 16-week intervention study. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31 (2), 121–34.

Mayo Clinic. 2020. Stress, depression and the holidays: Tips for coping. Accessed Aug. 3, 2021: mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20047544.

Ochentel, O., Humphrey, C., & Pfeifer, K. 2018. Efficacy of exercise therapy in persons with burnout. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 17 (3), 475–84.

Rohleder, N. 2019. Stress and inflammation—the need to address the gap in the transition between acute and chronic stress effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 105, 164–71.

Song, H., et al. 2019. Stress related disorders and risk of cardiovascular disease: Population based, sibling controlled cohort study. BMJ, 365 l1255.

Tawakol, A., et al. 2017. Relation between resting amygdalar activity and cardiovascular events: A longitudinal and cohort study. The Lancet, 389, 834–45.

Len Kravitz, PhD

Len Kravitz, PhD is a professor and program coordinator of exercise science at the University of New Mexico where he recently received the Presidential Award of Distinction and the Outstanding Teacher of the Year award. In addition to being a 2016 inductee into the National Fitness Hall of Fame, Dr. Kravitz was awarded the Fitness Educator of the Year by the American Council on Exercise. Just recently, ACSM honored him with writing the 'Paper of the Year' for the ACSM Health and Fitness Journal.

Thea M. Benally

Thea M. Benally is completing her bachelor of science degree in exercise science with a minor in population health at the University of New Mexico. Her research interests include exercise for clinical populations, physical therapy rehabilitation for patients with cardiovascular disease, and endocrinology research, specifically in American Indian populations.