School of Fish

Upgrade your diet with the most nutritious and sustainable seafood.

Seafood can be a culinary Jekyll and Hyde.

While most fish species boast a nutritional profile that outclasses meats like beef and chicken, industrial-scale fishing can carry a heavy environmental burden. And some fish are swimming with contaminants you don’t want in your diet.

But there’s no need to spurn seafood entirely. Just get better informed so you can make the best choices for you and the planet. Following these rules can help:

Eat More

On average, the typical American diet provides one 4- to 5-ounce serving of seafood a week—well below the American Heart Association’s recommendation of 7 ounces per week for adults (AHA 2016). We eat about 15.5 pounds of fish per year (National Marine Fisheries Service 2016), compared with the 51.5 pounds of beef—leaving plenty of room to swap steak for salmon more often. And there’s encouragement to do this: A study in Great Britain found that eating less beef improved people’s risk for heart attack, whereas eating less fish increased their coronary woes (Würtz et al. 2016). The vaunted Mediterranean Diet, which has been linked to better heart and brain health, is typically much more fish-centric than the standard chicken-heavy American buffet. The upshot is that many people would be well served by getting more seafood into their meals.

Go Mega on Omega-3s

Research has widely recognized that marine-sourced omega-3 fatty acids are crucial to good health. Sufficient intakes are linked to improved heart and brain health (Amen et al. 2017; Kris-Etherton, Harris & Appel 2002; Maki et al. 2017), lower inflammation (Rodríguez-Cruz & Solis Serna 2017) and less risk for hearing loss (Curhan et al. 2014). Research suggests that healthy intakes of these fats can also lessen postexercise muscle pain (Lembke et al. 2014) and perhaps bolster blood flow in athletes to improve exercise performance. The best sources of omega-

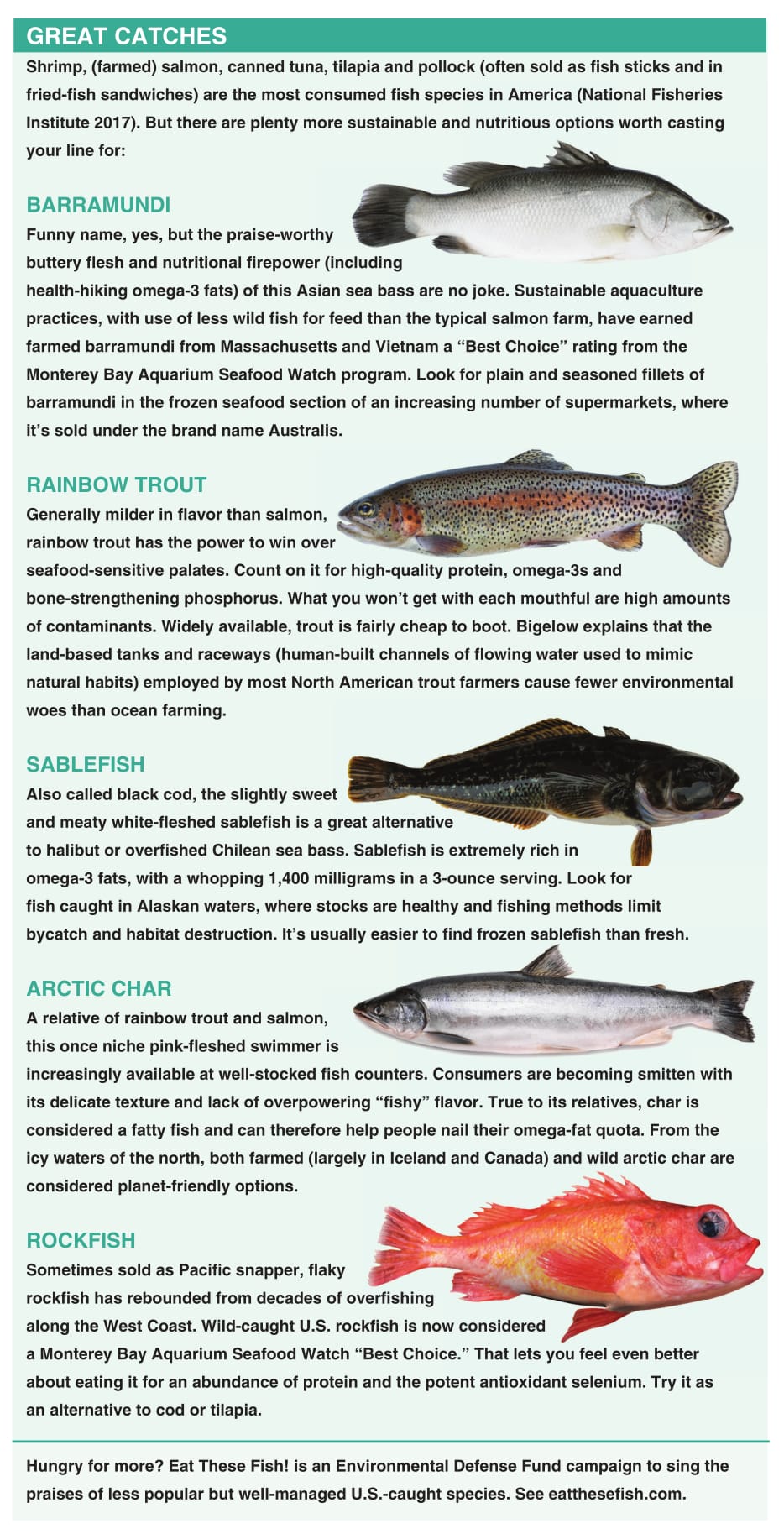

3s include salmon, sardines, mackerel, barramundi, sablefish (black cod), herring, rainbow trout, arctic char and some species of tuna. Omega-poor choices include shrimp, tilapia, cod and pollock (usually the main ingredient in fish sticks and fried-fish sandwiches) (AHA 2016; Delaware Sea Grant 2017).

Shrink Your Shrimp Intake

Shrimp is the most-consumed marine nibble in the United States, with the average American eating about 4 pounds a year (National Fisheries Institute 2017). But our hunger for shrimp often has environmental and human welfare costs. “Liberal use of chemicals such as antibiotics, waste discharge into surrounding waterways and human rights issues such as forced labor can be concerns with overseas shrimp farms,” says Ryan Bigelow of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch program. Shrimp does have vitamin D, protein and iron, but frying shrimp or soaking it in cream sauce cancels the nutritional benefits.

Bigelow suggests consuming domestic wild or farmed shrimp when available. “Generally, North America has much stricter regulations with respect to shrimp fishing and farming practices,” he says (see seafoodwatch.org for more guidance).

Go Wild for Salmon

The rising tide of aquaculture is making salmon a cheaper, ubiquitous addition to seafood counters. Rich in protein, omegas, B vitamins and antioxidants, salmon has one of the best omega-3-to-mercury ratios of all seafood options (IOM 2007).

But Bigelow notes that depending on country of origin, concerns about farm-raised salmon—such as chemical use, escapes into the wild, the spread of diseases in cramped pens and the use of high amounts of wild feed—still persist. “This is why most farmed salmon is still on our red ‘avoid’ list.”

For sounder fishing practices, splurge on wild Alaskan salmon species like chinook (or king) and sockeye (salmon labeled “Atlantic” is farmed). Bigelow says Alaska’s salmon fishery is well managed with strict rules, including catch limits that maintain a healthy population.

Flex Your Mussels

Mussels, the briny shellfish found at most fish counters, pack a sustainable, nutritional punch, with ample omega-3 fats and a boatload of protein, antioxidants and vitamin B12. Nearly all mussels on sale are farmed, but that’s something to celebrate.

“When suspended in waterways, mussels require no supplemental feed; they filter water to actually make it cleaner, [and they] require few chemicals to keep diseases at bay,” says Bigelow. “With mussels, you can get a lot of protein in a very small space.” And if you purchase farmed mussels, they barely have any grit to remove at all.

Clams and oysters are similarly nutritious and sustainable, but mussels tend to be easier on your food budget.

Be a Can-Do Person

For a convenient, budget-friendly way to eat more seafood, don’t skip the canned-fish aisle at the store. Some of the most nutrient-dense and sustainable seafood options are canned sardines, canned mackerel and canned salmon. For instance, canned sardines are a fantastic source of hard-to-get vitamin D, while tuna offers a boatload of muscle-building protein. And almost all canned salmon comes from sustainable wild stocks.

Consider buying from smaller companies that commit to sourcing fish only from healthy stocks; employ better fishing methods, like pole-and-line; and, in the case of tuna, pack cans with younger, smaller fish that have fewer contaminants. Bigelow also suggests looking for tins of tuna labeled “FAD Free” or “Free-School,” which point to more sustainable fishing methods.

Don’t Play Heavy Metal

Fish can be tainted with toxins like mercury and dioxins—because waterways are. Thus, the seafood counter is a potential source of toxins that have been linked to neurological problems, increased risk for diabetes and heart disease, and delayed brain development in infants (Genchi et al. 2017; He et al. 2013; Houston 2011).

While it’s believed that the health benefits of eating fish generally outweigh the risk from contaminants (Mozaffarian & Rimm 2006), you can still tailor your dining habits to avoid toxins. Since larger, longer-living predatory fish tend to have higher concentrations of mercury, try eating less shark, swordfish, king mackerel, marlin, orange roughy, tilefish and tuna (bluefin and bigeye). Canned “white tuna” is larger albacore tuna that may have absorbed more mercury than the smaller skipjack tuna primarily used in “light tuna” (seafoodhealthfacts.org).

Think Smaller

Oily fish like Atlantic herring, Pacific sardines, smelt and anchovies may be small (and, undeniably, somewhat stinky), but they’re nutritionally huge—with impressive amounts of fab fats, protein, minerals and vitamin D. And with short lives and less body weight, they don’t accumulate much in the way of toxins. Moreover, they are some of the cheapest proteins around. Canned sardines are easy to add to sandwiches and pasta dishes, anchovies dissolve into sauces and dressings for a shot of umami, and Scandinavians praise pickled herring on crackers and open-faced rye sandwiches. You may want to start with small amounts of these fish until you get used to their stronger flavors.

Shop Close to Home

Though the vast majority of seafood served in America is imported, Bigelow recommends seeking out American-caught options because U.S. fisheries have some of the world’s strictest regulations. Laudable progress has been made toward moving away from destructive fishing practices and unsavory farming methods, as well as rebuilding wild fish stocks. To find the best catches, troll for a business with a Seafood Watch partnership. Also look for labels with a certification like Marine Stewardship Certification, Wild American Shrimp, Aquaculture Stewardship Council or Global Aquaculture Alliance, all of which indicate reputable sources. While many people trumpet wild fish as a better catch than farmed, there are several instances where U.S. farmed is a smart choice; rainbow trout, tilapia and mussels are examples.

Don’t Be Fresh Obsessed

A lot of the “fresh” fish at the store was frozen for shipping and then thawed for display. “This is helpful in killing off parasites,” says Bigelow. The upshot is that the vacuum-sealed salmon or scallops in the freezer aisle may be a bit fresher than what’s sold as “fresh” (but has actually been sitting around on a bed of ice for a day or two). State-of-the-art flash-freezing technology employed shortly after fish are caught results in little if any loss of quality. Fish that isn’t fresh may have dry or dull-looking flesh or skin and, if sold whole, eyes that appear murky or cloudy. Seafood should smell briny like the ocean and not fishy.

Matthew Kadey, MS, RD

Matthew Kadey, MS, RD, is a James Beard Award–winning food journalist, dietitian and author of the cookbook Rocket Fuel: Power-Packed Food for Sport + Adventure (VeloPress 2016). He has written for dozens of magazines, including Runner’s World, Men’s Health, Shape, Men’s Fitness and Muscle and Fitness.