The Fourth Trimester: Postpartum Exercise

Why you need a big-picture approach to helping women get back on the fitness track after childbirth.

It’s not over in 9 months. A new mother’s body keeps changing long after the baby arrives. Hormonal shifts, breastfeeding and risks like pelvic organ prolapse (see “3 Issues for Postpartum Exercisers,” below) complicate the weeks and months after childbirth.

Yes, new moms want to shed the baby weight, but that needs to happen in the context of their still-changing physiology. Instead of focusing strictly on physical movements, I recommend a more holistic approach to postpartum exercise, addressing the most important physiological changes and modifying exercises to suit the realities of birth recovery.

New mothers often injure themselves because they jump back into fitness too fast, too hard and too soon. That’s more trouble than they need right after giving birth.

The Right Pace for Postpartum Fitness

Many new moms think that once the baby arrives, they should get back into their fitness routines and restore their prebaby bodies as soon as possible. The challenge is that the physical, emotional and hormonal impacts of pregnancy can extend weeks and months postpartum—and sometimes longer (HHS 2018). Understanding the changes that occur in the “fourth trimester” can help you to empathize with a new mom’s experience. These are some of the issues that may cause discomfort in the first year after childbirth:

- lower-back pain

- wrist pain or carpal tunnel syndrome (see below)

- ankle swelling

- sciatica

- incontinence

- neck pain

- difficulty lifting

- difficulty sleeping

- hormonal fluctuations

- weak transversus abdominis, multifidus and pelvic-floor muscles (see below)

- tight hamstrings and pectoralis muscles

- weak quadriceps and rhomboids

The frequency, intensity and duration of these issues can vary tremendously from one woman to the next. Other variables influencing birth recovery include the mother’s health and fitness before pregnancy, the number of previous pregnancies (and live births), complications during pregnancy/delivery, the labor and delivery experience, the postpartum bonding experience, and support from family and friends.

See also: Postpartum Core Support

Stability and Laxity Challenges

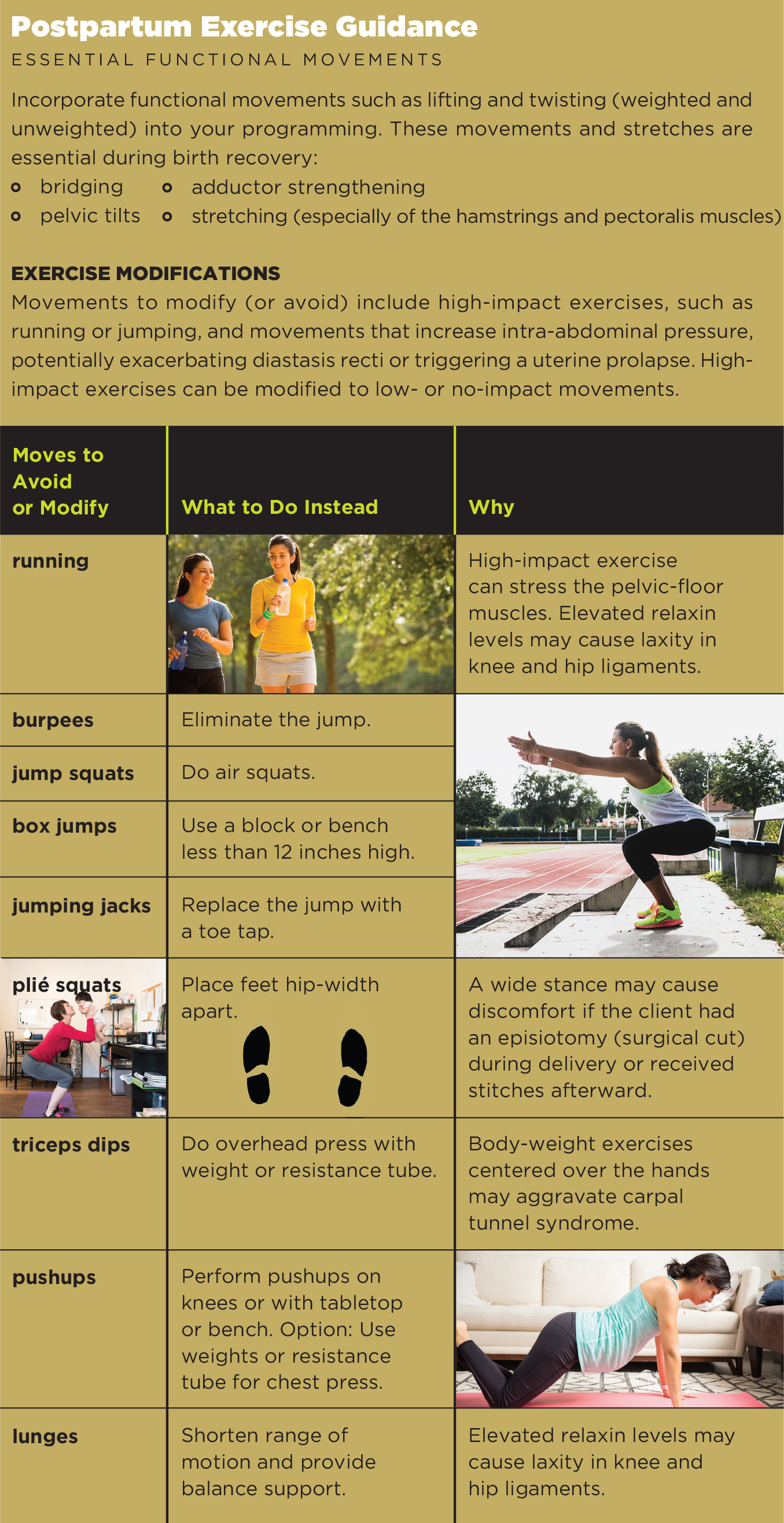

Physiological changes during pregnancy may reduce stability in joints and create laxity in ligaments and muscles (Reese & Casey 2015). Be cautious when developing exercise programming, as increased laxity may cause hip or knee pain during exercise. Limiting range of motion and reducing impact and load in various movements can help prevent pain and injury. Including warmups and stretching is more important than ever, especially for the hamstrings and lower-back muscles.

Your postnatal clients may not be aware that things like hormonal fluctuations (more on this below) and lack of sleep can increase the risk of injury while exercising. Thus, it’s crucial to modify exercises (see “Postpartum Exercise Guidance,” below) that may cause pain or discomfort or elevate injury risks.

Breastfeeding and Exercise

Breastfeeding can be a sensitive subject, especially for those who feel pain or discomfort with nursing. Still, there are many excellent reasons to encourage a breastfeeding client to continue with it as long as possible (Cleveland Clinic 2018). For instance, apart from the known health benefits of breastfeeding for the baby, nursing moms have higher caloric (energy) requirements after the child is born, which may help with shedding postpartum pounds.

Remember that exercise can be uncomfortable with full breasts. Encourage nursing moms to breastfeed or pump as close to the beginning of a training session as possible. Although high lactic acid levels in breast milk (due to exercise) may have been a concern in the past, we’ve known for some time that these levels drop quickly after a moderate-intensity workout (Carey, Quinn & Goodwin 1997).

Proper support, such as a nursing bra plus an exercise bra, may improve a breastfeeding mom’s comfort level. Breast pain and tenderness may mean she has mastitis, in which case she should not exercise. She should go home, rest, hydrate, apply heat, feed her baby and pump, and call her physician (Murray 2018).

Hormonal Shifts

Many pregnancy-related hormones remain active throughout the postpartum period. For instance, breastfeeding triggers the hormones prolactin and oxytocin, which suppress the menstrual cycle, aid in the birth recovery process, and encourage bonding between mother and baby (WHO 2009). Hormones that increase during pregnancy and then reshift postpartum include estrogen, progesterone, relaxin and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Tal et al. 2015).

THE MAJOR ROLE OF RELAXIN

Relaxin helps loosen ligaments and joints throughout the body (Reese & Casey 2015). Most importantly, relaxin causes the pelvis to relax, helping to increase pelvic diameters and allow passage of the baby at birth.

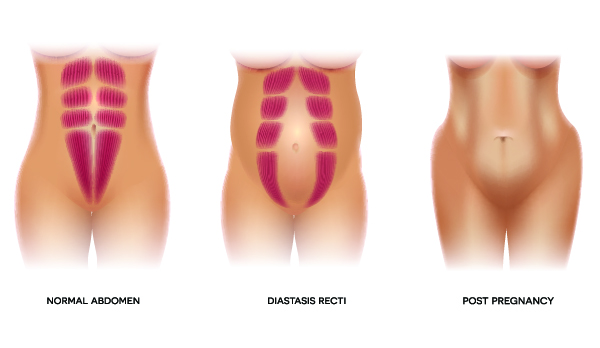

Higher levels of relaxin may cause systemic joint laxity, weakening of pelvic-floor muscles, diastasis recti (above), and even postural increases in lumbar lordosis (excessive curve of the lower back) and thoracic kyphosis (outward curve of the upper spine). Knees, hips, elbows, wrists and pelvic articulations are vulnerable to higher relaxin levels, as well. Relaxin also loosens ligaments in the feet, which is why many women have a permanent increase in shoe size.

Relaxin levels decrease as the frequency of breastfeeding declines, especially as the baby begins eating solid food at around 6–8 months old.

See also: Yoga as Therapy for Postpartum Clients

Emotional and Social Issues

Be sensitive to the emotional and social challenges new moms face.

- Whether you have had a baby or not, avoid the temptation to give parenting advice.

- Keep in mind that new moms often struggle with body image and clothing options. Encourage them to be patient and stay off the scale.

- Ask about sleep deprivation—it’s a normal part of being a new mom. Moderate exercise helps provide higher-quality sleep, so urge clients to stay consistent with their physical activity.

- Remember that hormonal fluctuations and emotional swings are normal.

- Encourage clients to join a mom’s group or a mom-and-baby fitness class. Support from family, friends and other new moms is essential.

3 Issues for Postpartum Exercisers

DIASTASIS RECTI (DR)

DR develops when the connective tissues between the right and left rectus abdominis separate during late pregnancy. Assessing the severity of DR, based on a finger-width scale, is a task for a trained professional. A study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine showed that about 60% of women have DR 6 weeks after giving birth (Sperstad et al. 2016). Although DR is most common in postpartum women and athletes, it may also occur in men and children. New moms may have a higher risk for DR if they have had two or more pregnancies, have gone through recurrent abdominal surgeries or did not get prenatal exercise (Turan et al. 2011; Spitznagle, Leong & Van Dillen 2007).

Assume a client under 16 weeks postpartum has DR.

Movement tips:

- Begin by helping her with breath work focused on engaging the transversus abdominis muscles (TVA) before progressing to more challenging core exercises. Movements that increase intra-abdominal pressure can exacerbate DR.

- Focus on slow, controlled movements that strengthen the TVA and obliques.

- Maintain rib cage alignment and avoid flaring the rib cage.

- Incorporate pelvic tilts (standing or supine) and bridging movements.

- Initiate movement from the abdominals and focus on using the breath (exhalation) to engage the TVA.

- Remind your client to stand (and sit) tall.

- Avoid full crunches and spinal flexion.

See also: Abdominal Separation and the Female Core

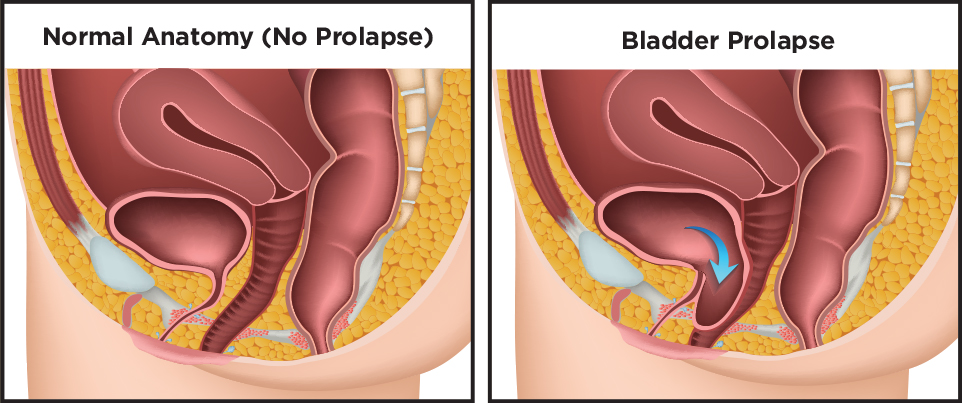

PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE (POP)

Childbirth, especially vaginal delivery, increases the risk of POP (Nygaard et al. 2014). A prolapse can occur when one or more organs drop from their normal position. This can result in pelvic pain, discomfort during intercourse, frequent urinary tract infections, and/or a protrusion or bulging of organs from the vagina. Returning to high-impact exercises such as running or jumping too soon after childbirth can increase the likelihood of POP.

CARPAL TUNNEL SYNDROME (CTS)

A study from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran, showed that CTS developed in about 19% of the pregnant women who participated; and more than 26% of cases were severe (Khosrawi & Maghrouri 2012). Although CTS tends to resolve itself after delivery, breastfeeding women often experience a longer recovery period because of the position in which they hold their babies and the impact of the hormone relaxin. Exercises such as pushups, triceps dips and full planks may aggravate CTS. Modify exercises so your clients can strengthen similar muscle groups without increasing pressure on the wrists and median nerve.

Exercise After Pregnancy: The Basics

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists maintains an online list of frequently asked questions about labor, delivery and postpartum care. See FAQ131, Exercise After Pregnancy, for a solid introduction to the fitness concerns of new moms.

Putting It All Together

There is no reason to be afraid of training a client who recently gave birth. As her trainer, you may have to encourage her to slow down and to resume exercise in a safe and effective manner. Remind her that her pregnancy lasted 40 weeks, and it is realistic to spend the next 12 months working to slowly improve her strength and endurance. With consistency and patience, she can become stronger than she was before she got pregnant. Many moms do.

Kristen Horler, MS

Kristen Horler is the CEO and founder of Baby Boot Camp, a fitness franchise for moms. Learn more at babybootcamp.com.